Tag Archives: living in Italy

How to Use the Milan Metro

updated Oct 18, 2006 – prices could well be out of date by now!

The Milan metro is moving to a smart card system for local passengers with monthly or annual passes. This is fine for the locals, but the authorities, in their infinite wisdom, have also removed the old ticket machines from most metro stations. The new orange machines can only be used for smart card refills, and to buy single tickets for INTRA-urban (within city) trips – which, unfortunately, leaves out the new fair/expo complex at Rho. Most of the machines to stamp paper tickets at the turnstiles have also been replaced by smart card readers.

For Business Travellers to Rho/Fiera

The new regime has created a problem, particularly at Milan’s Central Station where many business travellers arrive. You can buy paper tickets from the big edicola (newsstand) in the middle of the mezzanine floor in the metro station (and maybe in the edicole in the railway station itself).

The prices for Rho are:

- 2 euros – single trip

- 5.50 euros – 24 hours’ unlimited use

- 9.70 euros – pass good for a week

During big expos, the edicola in the metro has three ticket windows operating, but there can still be very long lines.

If you walk around the corner to the right of the edicola, you will find a few of the old ticket machines which still sell all kinds of tickets – when they work, and IF you can figure out (in Italian) how to use them (the options seem immensely complex). These machines issue old-fashioned paper tickets which must be stamped in one of the few remaining ticket stampers – look for the little yellow boxes perched on top of the turnstiles nearest to the operator booth in the center of the concourse.

During fair times I also see people lined up at the new orange machines. I don’t know what happens if you buy one of the new intra-urban tickets and then travel all the way to Rho. In any case, if you buy one of these tickets, you slide it into the little slot on the front of the turnstile.

Your best bet is to try to get tickets BEFORE you get to Milan’s Central Station; many other newstands and tabaccai (tobacco shops) supply them – be sure to specify that you’re going to the fiera [FYAIR-ah] in Rho.

If you are staying out of town and commuting into Milan, it is often possible to buy Milan metro tickets at outlying railway stations; ask in the edicola at the station.

Getting to the Fair

Once you’ve got your ticket, go through the turnstiles to the left of the information booth. Immediately after you’ll see a staircase going down on your right. This takes you to the green line (Linea 2) of the metro going in the direction of Abbiategrasso.

Take this line five stops to Cadorna.

Change to the red line (Linea 1) in the direction of Rho/Fiera (obviously), which is the end of the line, so you can’t miss your stop.

See below for instructions on finding the right platform and train.

For Travelers Within Milan City

If you’re going to be using Milan’s public transit system (metro and/or buses and/or trams) more than three times on a given day, buy a day pass (3 euros, last time I looked). If you’re going to be using the system for multiple days but only twice a day, you can buy a ten-ride ticket from the orange machines.

Single and multiple tickets are good for 75 minutes throughout the system – run the ticket through the machine the first time you get on a bus or tram AND the first time you go into the metro. The ticket is good throughout the metro system as long as you stay underground (don’t pass the turnstiles), but once you have exited the metro you’ll need to use another ticket to re-enter, even if your original ticket still has time on it. However, you can keep riding on the buses and trams until your time’s up.

Figuring Out Which Train to Take

There are three metro lines – red, green, and yellow, aka Linea 1, 2 and 3.

The red line runs from Sesto (aka Sesto San Giovanni, a suburb of Milan) – Primo Maggio in the north, through the city center (Duomo) and out of the city again to the west. It splits at Pagano, with one line going northwest to Rho/Fiera (the new expo) and the other southwest to Bisceglie. So, if you’re heading west past Pagano, make sure you choose the right train! The final destination of the next train will be shown on the lighted display above the platform as the train pulls in, and also on signs on the front and sides of the train itself.

The green line runs from Abbiategrasso, south of Milan, passing through the city center and the Central Station. Heading east, the line splits at Cascina Gobba and goes to either Cologno Nord or Gessate. If you will be going east past Cascina Gobba, make sure you choose the right train!

If you do make a mistake and board the wrong train, get off as soon as you realize it. If you haven’t passed the station where the line splits, you can simply wait on the same platform for a train going to the right place, which is usually (but not always!) the next train to come along. If you have passed the split, you’ll need to go back the way you came until the split, then take the correct train.

The yellow line runs from Maciachini in the north to San Donato in the south, with no splits.

The lines intersect as follows:

- red and green: at Loreto and Cadorna

- green and yellow: at Stazione Centrale

- red and yellow: at Duomo

You can change trains (using the same ticket) at any of these intersections.

How to Find the Right Train

As you enter the metro station, look for signs overhead pointing to the train in the direction you want to go, which will be identified by the name of the station at the end of the line.

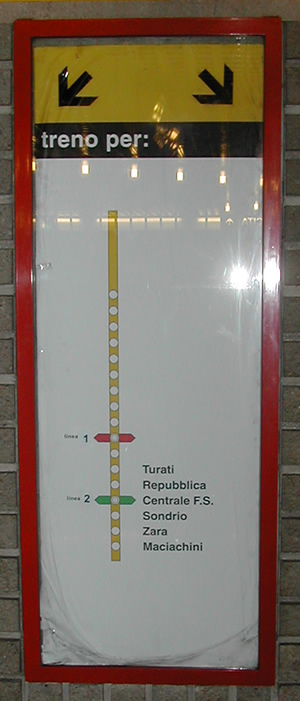

Then look for a sign like the one above. This example is a sign at the Montenapoleone station on the yellow line, showing the stops remaining in the northward direction to Maciachini. There are six stops remaining, and the yellow line will intersect with the green line at Centrale FS (the Central Station).

add your own Milan metro tips below!

La Buona Educazione: Good Manners in Italy

Italy has four or five of those freebie newspapers, you probably have them in your city as well. The one I read regularly is Metro, partly because it’s the best of a bad lot, partly because it’s the only one distributed at the Lecco railway station. It’s not serious news, just enough to keep up on showbiz silliness (Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie will get married on Lake Como next week – wait, no, they didn’t), and the letters page is a glimpse into what’s on the collective Italian mind.

Every now and then they publish a flurry of letters about manners, usually started by a woman complaining that no one, and especially no man, ever offers her a seat on the bus or subway – even when she’s visibly pregnant. Other women chime in with similar experiences, then the men recount how no one ever gave them a seat, even when they were on crutches, or how some women are snappishly offended to be classified as old enough to need such courtesies.

How well I remember traversing the city every day to daycare, standing with a heavy two-year-old Rossella in my arms because, if I put her down, she was likely to get stepped on or bashed in the head with someone’s heavy bag.

Once she asked, in a loud, clear voice: “Why won’t anyone let us sit down?” (This was during the phase when she only spoke Italian, so everyone understood it.)

“Because,” I answered equally loudly, and in Italian, “no one is civil enough to notice that there’s a mother here with a child in her arms who needs to sit down.”

That finally got us a seat.

During my recent visit to Texas, I was startled that men kept leaping ahead to open doors for me. This reminded me of a fellow Woodstocker who had attended the University of Texas at the same time I did. He was Bangladeshi, and had some cultural adjustment difficulties. He said to me mournfully: “I never know what to do at a door. If I don’t open a door for a girl, she gives me a dirty look. If I do, she calls me a chauvinist pig.” (I told him that he should do what was right for him, and if someone called him a pig for his good manners, she was seriously lacking in manners herself.)

The nagging problem on trains is many passengers’ failure to close the compartment doors. On a typical commuter train, each carriage divided into three sections, with two entry platforms, plus doors on each end into the next carriage. The entry platforms are not heated, so in winter it’s important to close the doors between the compartments and the entryways. (They should theoretically close by themselves, but the trains are so old that they often need a push.)

But lots of people go charging through the train, leaving a string of open doors behind them, and other passengers shouting irately after them: “Ehi! Porta!” (“Hey! Door!”) – usually ignored, because someone who is rude in the first place is rarely going to acknowledge the fact and correct his error.

I habitually sit near the door, so am often the one to get up and close it. A few times I have commented to a nearby passenger: “Tutti nati in stalla,” from the American: “Were you born in a barn?” This phrase isn’t used in Italy, so Italians find it very funny; Ross’ boyfriend doubled up laughing the first time he heard it.

Talking Back to Politicians: A Lesson in Modern Italian

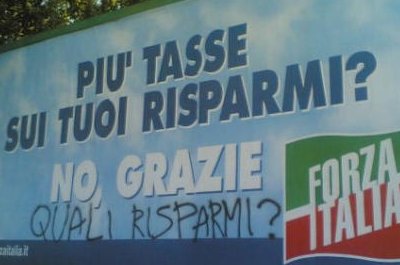

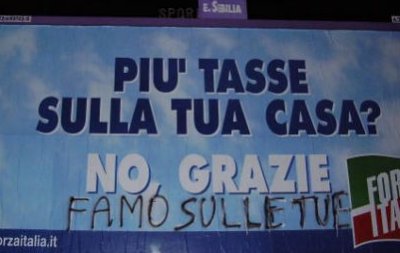

^ top: “More taxes on your savings? No, thanks!” To which someone has responded: “What savings?”

Italy doesn’t yet have a large enough Internet population to spawn interesting multimedia political parodists like JibJab. But citizens nonetheless find ways of talking back to their politicians…

Note: All these pictures were posted by readers on the site of Il Corriere della Sera (under “Elaborazioni fotografiche”).

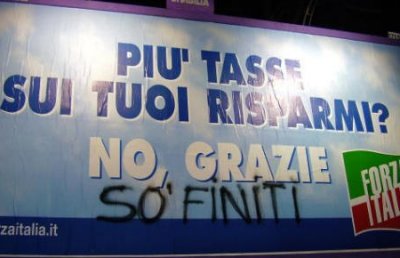

Forza Italia (Berlusconi’s party) have done a series of posters with the theme “No, Grazie” (No, thanks) about all the terrible things that will supposedly happen if the left is elected.

^ Same original poster, this time with the response: So’ finiti, Roman dialect for “Sono finiti” – they [the savings] are finished (used up).

^ “More taxes on your home? No, thanks.” “Let’s tax yours.”

Famo = Roman dialect for facciamo – let’s do it. Le tue [case] refers to Berlusconi’s homes. Homes plural – he has several. Not that this is unusual in Italy, but his are rather bigger than anybody else’s…

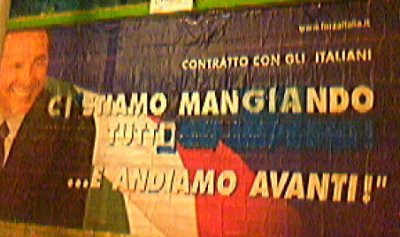

^ The original text reads: “Contract with the Italians. We are keeping all our promises!” Someone has inserted: “to our buddies.”

Final (original) line: “And we’re going ahead!”

^ The same poster, altered to read: “We’re eating everything – and we’ll continue!”

^ “Neighborhood police and carabinieri are now in every city” …and they still haven’t found you.”

^ This one originally read: “Let’s choose to go on/move ahead.”It now says: “Let’s choose to steal a lot.”

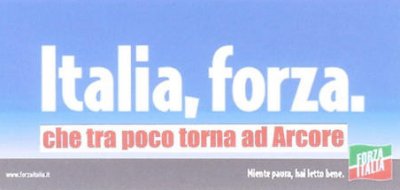

Forza Italia’s name is also a slogan, roughly translatable as “Let’s go, Italy!” (forza is what you say to urge on your sports team).

For this campaign they’ve turned it around so that it reads like an admonishment to a recalcitrant child: “Come on, Italy.” Or encouragement to someone very tired: “Come on, you can make it.”

With the added text, this translates as: “Hang in there, Italy – soon he’ll go home to Arcore.” (Arcore, near Milan, is the site of Berlusconi’s biggest villa.)

^ Casini, head of another party in Berlusconi’s coalition, claims [to have] a “A different idea.” Comment: “If only you had one.”

^ “More support for the family” …of Berlusconi.”

And, for the opposition, my personal favorite:

Italian Surnames: The Funny, Surprising, and Just Plain Weird

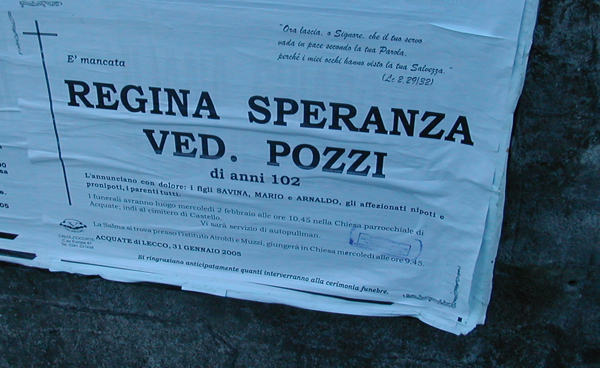

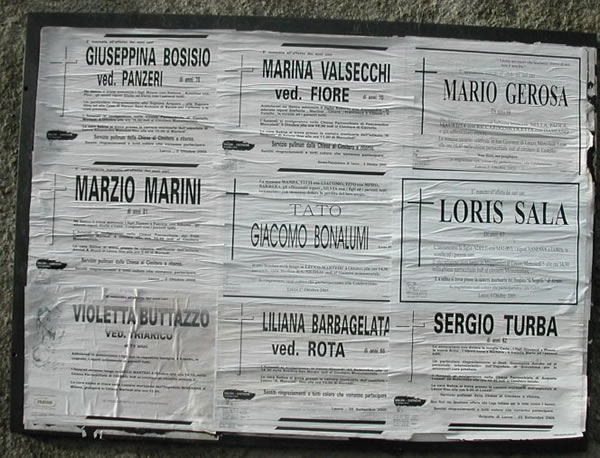

^above “Queen Hope, widow of Wells” – she lived a good long life!

Il Corriere della Sera reports today that Italy has the largest number of surnames in the world: 350,000. The ten commonest surnames cover only 1% of the population. And, with many surnames, you can also tell something about its origins by its ending.

Italian surnames are fascinating, and sometimes very funny. Some of the best don’t seem to have emigrated to the US, though Americans trying to pronounce their Italian surnames can also be funny. I met a photographer in Connecticutt with the wonderfully romantic surname “Mezzanotte” (Midnight). An Italian would pronounce this Med-za-NOT-tay, which also sounds lovely. He pronounced it Mezza-note, which doesn’t.

One of the most common surnames in Lombardy is Fumagalli, which translates literally as “smoke the chickens.” That is: blow smoke into the henhouse to stun them, so they don’t make noise while you’re carrying them away. I guess chicken thieving was common in Lombardy, hence the popular Italian saying, Conosco i miei polli (“I know my own chickens”), used when you can predict how someone will behave or react, because you know them so well.

Death announcements in Lecco. Note the surnames Turba (“disturbs”) and Barbagelata (“frozen beard”)

I can’t think of examples of names in America which have a funny meaning, although some non-English names sound funny or rude to an English speaker, such as the Jewish Lipschitz or Indian Dixit (pronounced Dickshit). In Italy, there are many names which sound funny or odd even to Italian speakers, and leave you wondering how somebody’s ancestor acquired it. Examples:

- Squarcialupi – “squarciare” is to rip, with violence; “lupi” are wolves. Okay, the ancestor was a fierce hunter.

- On the other hand, Cantalupi – “cantare” – to sing. Sings with wolves?

- Pelagatti – “pelare” – to peel or skin, “gatti” …cats. Presumably this guy knew more than one way.

- Pelaratti – same thing, but rats. Now why would you bother?

Then there are the surnames which Italians fervently wish they could change, and go to great lengths to do so (it’s not easy to change a name in Italy), such as Finocchio – “Fennel,” but it’s also common slang for gay. Most red-blooded Italian males don’t want this one!

A friend of ours once worked in the office in Rome where name changes are (rarely) approved. He told us the most egregious case he ever came across was the name “Ficarotta” – broken cunt. The change was allowed.

More Funny Italian Surnames

- Malinconico – melancholy

- Mezzasalma – half-cadaver

- Tagliabue – ox-cutter (butcher, I suppose)

- Bellagamba – beautiful leg (there was a famous cardinal of this name)

- Caporaso – shaved head

- Denaro – money – a Mafia family in the news!

- Contestabile – debatable

- Falaguerra – make war

…but…

Acquistapace – buy peace - Accusato – accused

- Peccati – sins

- Bonanno – buon anno – good year, or happy new year

- Borriposi – buon riposi – good rests

^ This architect’s surname means “big tower”.

^ “Macelleria Pancioni” would be literally translated as “big bellies butcher,” though Pancioni is probably a family name.

Nov 23, 2003

Many Italian surnames are also common words, so the potential for comedy is enormous when juxtaposed with the person’s profession, residence, or spouse. One of the funniest books we own is Mal Cognome Mezzo Gaudio, by Antonio di Stefano. The title is a pun on the saying Mal commune mezzo gaudio (A shared sorrow is half a joy); cognome means surname. The book is a treasure trove of funny names and even funnier combinations. But he missed one of my old favorites, a shop near my in-laws’ place in Rome called Enoteca Bevilacqua – the Drinkwater Wineshop.

Another name that’s funny on its own is Cazzaniga. This Lombard name may not actually mean anything, but it sounds close to cazzo negro – black dick. So there’s a common joke about it: Cazzaniga? Che nome lungo. (“What a long name.”)

where do people with your surname live in Italy?

^ I assume this optical shop is named for its owner, whose surname means a joke or a trick.

^ This shop owner’s surname means “millet bread”.