One interesting and very successful aspect of Italian schools is how the entire system works to promote social cohesion among the students.

The basic unit at all school levels is the class – not in the sense of year (grade), but subsection of a year. There are usually multiple sections per year, identified by a number and a letter, e.g. Classe I C is section C of the first year. The following year this same group of kids will be section II C.

You are with the same people (including teachers) for all five years of elementary school, then change schools and find yourself in a new group for the three years of middle school. In five-year high schools, the classes stay together for the first two years (biennio), but may change composition for the last three years (triennio) if they subspecialize. For example, at the Liceo Artistico (art high school) that Ross attended, kids going into the third year had to choose between graphic arts, art history and conservation, and two other specializations that I don’t now remember.

There are minor changes to a class population each year because some kids repeat years (this happens frequently in high school) or change schools entirely (rarer) or move to a new town (extremely rare). But basically the same group of kids and teachers can expect to be together for years.

Each class does everything together, all day, staying more or less in the same room; it’s the teachers who go from classroom to classroom, except those whose subjects require labs or other special equipment.

Everyone in a section takes the same courses. There are almost no electives in Italian schools, since, by high school, you have chosen a specialized school and program which is hopefully what you’re interested in (if not, you have to change program or even school – difficult if you lack the prerequisites for the program you’d like to move into).

In public high schools, each class – by law – has two elected representatives, to protect the students’ interests within the institution. Each class may use two class periods per month for a class meeting in which to discuss class business, unencumbered by the presence of teachers. The representatives refer any complaints, troubles, or suggestions to their teacher committee or, if they think they won’t get a fair hearing from their teachers, to the principal. Class representatives meet regularly with their class’ teacher committee, and once each semester there’s an assembly of all class representatives in the school, headed by a pair of “institutional” representatives elected by the entire student body. Class representatives also attend the biannual parent-teacher meetings.

This gives students some direct and useful experience with leadership, representative government, and bureacracy. The elected leaders learn to deal with authority (we hope in a constructive manner). Class government helps to unite the class: they must act together to find solutions to problems, and elect leaders who can carry through those solutions effectively.

All these factors work to bind students into a cohesive social group; I assume that this is one of the basic, if undeclared, aims of the Italian education system.

And there is little going on in Italian schools that would tend to work against class cohesion: very few extra-curricular activities, no school sports except PE class, no band, cheerleaders, chess club, etc. All sports and hobbies are done as after-school lessons and activities (by those who are interested and can afford it). There are no school-sponsored dances or proms – anyone can go to a local disco, not even necessarily with a date.

Italian schools, quite reasonably, concentrate on academics, but not in the fiercely competitive way that seems to be the norm at some American schools. From what Ross tells me, there aren’t any publicly-recognized geniuses in Italian schools. Grading seems rather flat: on a scale of 1 to 10, 5 or lower is a failing grade, 6 is a bare pass, and most grades seem to fall in the 5 to 7 range – few 8s, fewer 9s, and I’ve rarely heard of any of Ross’ classmates (in any of her schools) getting a 10.

Italian schools don’t suffer anything like the clicquishness and bullying that characterize (some? many?) American schools. I won’t claim that no one ever gets teased nor feels excluded in any Italian school, but I have an attentive inside observer in Rossella, and she has never mentioned anything like the miseries that I went through in American elementary and middle schools. (Ross herself is keenly alert to that sort of thing, and works hard to integrate anyone she perceives as being excluded. That, and her let’s-fix-this-attitude, got her elected class rep last year.)

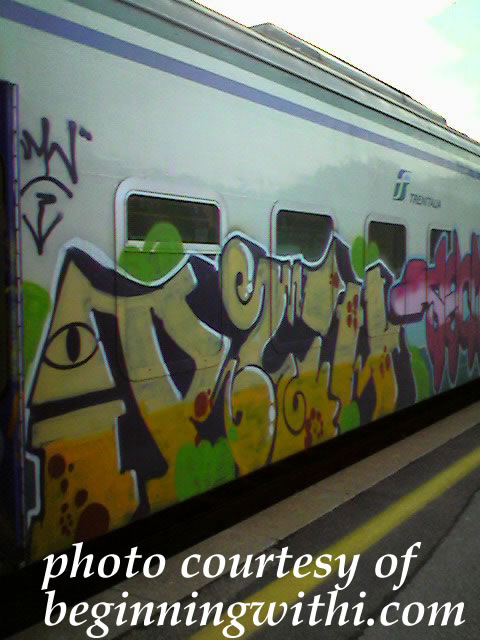

Physical violence and bullying in Italian schools are almost unknown. Rape or sexual harassment are unheard of. An Italian student is more likely to commit suicide (over bad grades) than to try to harm anyone else. They do get up to mischief, but it’s usually the school itself that suffers, in some form of vandalism. Sometimes students go on strike and take over the school completely, running classes themselves. (This seems to have gone out of fashion these days, but it’s an interesting illustration of student social cohesion.)

I’ve written a great deal about what I don’t like about the Italian education system, but when I see American kids passing through metal detectors to get into their schools, I heave a sign of relief and thanks that my daughter isn’t going through THAT.