| January | 1 – New Year’s Day6 – Epiphany | Smog Days | |

| February |  |

14 – San Valentino | |

| March |  |

8 – Festa della Donna(Women’s Day)Carnevale | Italian Winter Weather |

| April | Pasqua (Easter) | Holiday Treats | |

|

|||

| May |  |

1 – Labor Day | Cambio di Stagione |

| June | 2 – Republic Day |

||

July |

Air-ConditionedCommuting with NatureSummer Fun | ||

| August | 15 – FerragostoSummer Holidays | Feeling the SeasonsSummer Lovin’ | |

|

|||

| September | |||

| October | |||

November |

|||

December |

6 – San Nicolo’ (patron of Lecco)7 – Sant’ Ambrogio (patron of Milan)8 – Immaculate Conception

25 – Christmas 26 – Santo Stefano 31 – Capo d’Anno |

Winter HolidaysBridging the HolidaysHoliday Hell | |

Tag Archives: living in Italy

Divorcing Italy

Rossella and I returned to Italy the week before Christmas, having been away since June 30th. That was the longest period I’d spent out of Italy in 18 years.

I was uneasy about this re-entry, expecting it to be traumatic. I thought I would be making a decision about whether I would ever willingly live in Italy again (not right away, but maybe, someday), and I didn’t expect that decision to be easy. But, in retrospect, I had probably made up my mind months – even years – before.

The immediate impact wasn’t good. I arrived exhausted (Rossella can sleep on planes; I am not so fortunate). We hadn’t even left the airport before Enrico was telling us about a typically Italian bureaucratic kerfuffle that had arisen just that morning and had him worried.

The weather was terrible most of the time I was in Europe: cold and gray, with unusual amounts of snow even for northern Italy. The humidity sank the cold into my very bones; I felt colder in Italy than I ever do in Colorado, where the absolute temperatures are often much lower.

As usual, we spent Christmas in Roseto degli Abruzzi, the small seaside resort where Enrico’s parents retired years ago. As usual, the town was dead and depressing in winter. As usual, Ross was agitating to leave almost as soon as the Christmas presents were opened, and I couldn’t blame her, especially when she learned that a friend’s mother had died.

We returned to Lecco, where I felt trapped by bad weather and my fear of driving in Italy (I may someday get used to this, if I could only have an automatic instead of a stickshift…). I realized that I had been feeling trapped for years.

Moving to Lecco was a good decision at the time. Milan’s pollution was killing me, Enrico’s job would be mostly in Lecco, and it was a good place for Ross to spend her teenage years – she had a lot more freedom there than we would have felt safe for her in Milan.

But Lecco is also a small, typically introverted Italian town. There’s not a lot to do there, we have hardly any local friends, and those tend to be busy with their jobs and extended families. We have given lots of dinner parties, but we rarely get invited back. With Ross gone, that leaves a lot of time when it’s just the two of us.

Lecco isn’t the only problem. By any measure, my career opportunities anywhere in Italy are scarce. I’m middle-aged, foreign, female, and opinionated, in a country where it is legal to specify “young and good-looking” in a want ad, and the current prime minister has appointed former showgirls of questionable qualifications to his cabinet, for very questionable reasons.

In “shocking but not surprising” news, a friend told me she recently saw a documentary on PBS which stated that female employment in Italy is at its lowest since WWII. I haven’t yet found any online corroboration for this, but do know that equal opportunities for women in Italy are nearly non-existent.

High-tech doesn’t do well in Italy, either. Although it’s a G8 country, Italy is only number 25 in an Economist Intelligence Unit ranking of IT competitiveness. In other words: not much original is going on there. Many large American/multinational high-tech firms (Cisco, HP, Sun, Microsoft) have offices in Italy, but those are primarily sales and support sites, not places where someone like me is likely to flourish. And they’re mostly in the suburbs of Milan, which would be at least a two-hour commute from Lecco, and put me right back into the pollution that was causing me so many health problems before.

All of these factors have been on my mind for some time. I’ve found lots of evidence to support my negative assessment of my chances in Italy. I freely admit to bias, but can anyone show me evidence to the contrary?

The upshot of it all is that I’m angry – very, very angry. And bitterly disappointed. If anyone should have done well in Italy, it was me. I speak the language fluently. I understand the culture. I gave one hell of a lot to Italy (including a horrendous amount of taxes on my American salaries), and got very little in return except years of frustration and underemployment. In the end, the only way to stay would have been to throw away 20+ years of work experience – work that I truly love – and do something that merely exploited my foreignness: teach English, run tours, write “Under the Lake Como Moon”, etc.

That I will not do.

So I’m divorcing Italy.

Not my Italian husband, mind. Living apart has been very hard on both of us but, for the time being, we’ve decided to try to stick it out.

But I’m definitely divorcing Italy. I’ll visit, as long as Enrico and friends and family are there, but I don’t expect to ever live there again (NB: I’ll be surprised if Ross does, either).

This decision comes with a raft of emotions, probably similar to those surrounding a divorce. Anger. Betrayal. “I gave you the best years of my life!” Sadness. Grief.

Italy has a lot going for it still, and, for some people, it’s their ideal place, even if they weren’t born there. I don’t deny that nor attempt to dissuade them. But, for me, it’s over. And that would be a painful revelation even without the complication of an Italian husband who still lives and works in Italy.

So if I’m not very enthusiastic (to put it mildly) about Italy these days, now you know why.

NB: A year and a half later, I left Enrico as well.

Italian Train Graffiti

I like graffiti art (when it’s good – not that stupid tagging crap) and photograph it whenever I can. These are examples I’ve collected over years of travelling and commuting by train in Italy.

- All about getting around on Italian Trains

What I Miss About Italy

unconscious (?) irony: a shop in downtown Milan displays this antelope head next to a photo of Brigitte Bardot, who, retired from acting, is a big animal rights activist

Since I moved (back) to the US earlier this year, a number of people have asked me what I miss about living in Italy. It’s a hard question, and part of my agenda for this trip was to try to answer it. Yesterday provided me with a mini case study on the matter.

Although you can find individual items discounted year-round, Italian retailers are allowed, by law, only two big sales periods during the year, in early January and early July. The exact dates are determined by local government, and this year the Milan sales began January 3rd. After a fairly disastrous Christmas season, and in a very gloomy economy, both shop owners and customers were looking forward to this.

I wasn’t – I hate crowds and am not a big fan of shopping, so this was a nightmare scenario for me. But my business wardrobe needs updating and I wouldn’t have any other time before I leave for Dublin Monday. So I headed off to Milan, where at least I could look forward to also seeing friends.

Enrico drove me to the Lecco train station, arriving with five minutes to spare for the train I wanted to catch. Usually five minutes is plenty of time to buy a ticket, stamp it in the “obliterator”, and get on the train. But only two of the three ticket windows were open – apparently this period up to the Epiphany (Jan 6th) is a semi-holiday for the railways, so they were short-staffed. Both open windows had longish lines which would take longer because people wanted to discuss their travel plans in detail.

Usually you can buy “kilometric” (25 km, 30 km, etc.) tickets from the newsstand in the station, but they were out of the 50 km ones I needed for Milan. I poked my nose into the line at a ticket window to ask if it would be possible to buy a ticket on the train.

“Sure you can,” said the railway employee sarcastically, “if you also want to pay a 50 euro fine.”

I had to run to another newsstand down on the corner to get the !$!#@$@# ticket – all of 3.60 euros’ worth. Then run back, stamp it, and get on the train, which left the platform two minutes later. And no one ever came to check that I even had a ticket.

The train was middling clean and decent. Toilet paper in the bathroom, but no water to flush or wash my hands. Graffiti on the seats and walls. The real problem, however, was the heating. It was on, but not strong enough to cope with a very cold day. I was wearing a heavy sweater and sat with my coat over my knees, but still felt cold throughout the hour-long trip.

I arrived at Porta Garibaldi, one of Milan’s train stations, and had to take the metro to get to my friend’s place for lunch. I’d need to switch from the green line to the red, which I should logically do at Piazzale Loreto. As I was waiting on the platform, I heard a garbled announcement (in Italian only) about trains not stopping at two different stations, including Loreto, due to “works.” I couldn’t understand enough to know whether this would affect me, but thought: “This must be a pre-announcement referring to some other day. They surely wouldn’t be blocking stations today, of all days?”

They would. The train sailed through Loreto station without stopping. There were men laying tile on the platform on that side. Passengers who needed to get to Loreto had to go to the next stop and catch a train back in the other direction (the platform on the other side was open). This on one of the busiest shopping days of the year, at one of the prime stops for Corso Buenos Aires, a favorite shopping area. For work that could have been done in the middle of the night when the Milan metro is closed anyway. Probably there are rules preventing the tile guys from working after hours. Score: union rules – ten; customer service – zero.

I reached my friend’s home and had a lovely lunch with him and others. Then I finally, reluctantly, tackled my shopping. I was supposed to meet Ross downtown, which required taking the (now even more crowded) metro. Corso Vittorio Emmanuele, a large pedestrian thoroughfare in the heart of Milan, was wall-to-wall people, many of them with lit cigarettes wafting smoke into my face. I saw two well-dressed young men who had stopped in the middle of the street to enjoy a snack of freshly-roasted chestnuts, and were casually dropping the shells on the ground.

Ross and I shopped for about two hours, an activity I find exhausting under the best of circumstances. And there is nowhere to sit in Italian stores. Italian retailers don’t seem to have grasped the idea that a tired shopper, given a chance to take a load off her feet for a few minutes, might feel refreshed enough to hang around and spend more money.

As the shops began to close, we made our way to the home of another set of friends for dinner. Enrico had come from Lecco with the car, so at least we didn’t have to wait in a cold station for a train to get back.

The summary of the day is that I was glad to see friends and spend time with my family, but the rest was non-stop hassle. Which pretty much sums up my feelings about Italy at the moment: there are people here I’m glad to see (which, for me, is true of many other places). Other than that, there’s not much I miss about living in Italy.

Apologia del Fascismo, in Flagrante

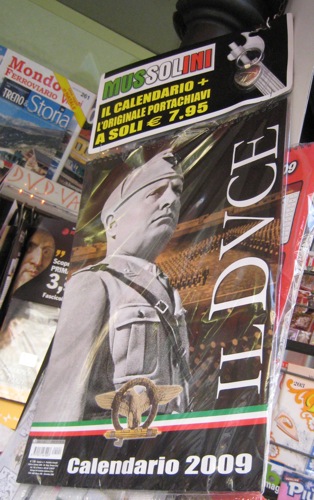

At this time of year, Italy’s newsstands offer a variety of calendars to suit every taste, from fast cars to naked women. But this one startled me, not least because it would seem to be in violation of Italy’s law against apologia del fascismo (“apology for Fascism”), which prescribes penalties against whoever “pubblicamente esalta esponenti, principi, fatti o metodi del fascismo, oppure le sue finalita’ antidemocratiche” – “publicly exalts exponents, principles, facts, or methods of Fascism, or its anti-democratic goals.”

According to Wikipedia, this law was watered down by subsequent court challenges to the point that defending Italian Fascism could only be considered a crime when such “exaltation” might lead to a refoundation of the original Fascist political party. Not likely to happen over a mere calendar, but the fact such a thing is openly offered for sale is enough to make me (and many Italians with longer memories) uncomfortable.

It seems obvious that the calendar (and other increasingly popular Fascist memorabilia) is designed to appeal to those Italians (e.g., young skinheads) who nostalgize about the Fascist period as a time of law and order and Italian martial glory – or, at least, a time when “the trains ran on time.” When the apologia law was instituted in 1952, Italians knew from direct and bitter experience that the Fascist period had been one of oppression and war which saw, among other horrors, the deportation of Italian Jews to German concentration camps.

Perhaps the Italian education system needs to spend a little less time on the glories of ancient Rome (Ross studied those in her first years of both middle school and high school), and more on the abominations committed by those who claimed to be following in Rome’s glorious footsteps. “Those who do not remember the past…”