This is often a low time of year for me. The days are getting shorter and colder; I wake up in darkness, leave the house in twilight, and by the time I get home it’s dark again. This is hard on my tropical psyche.

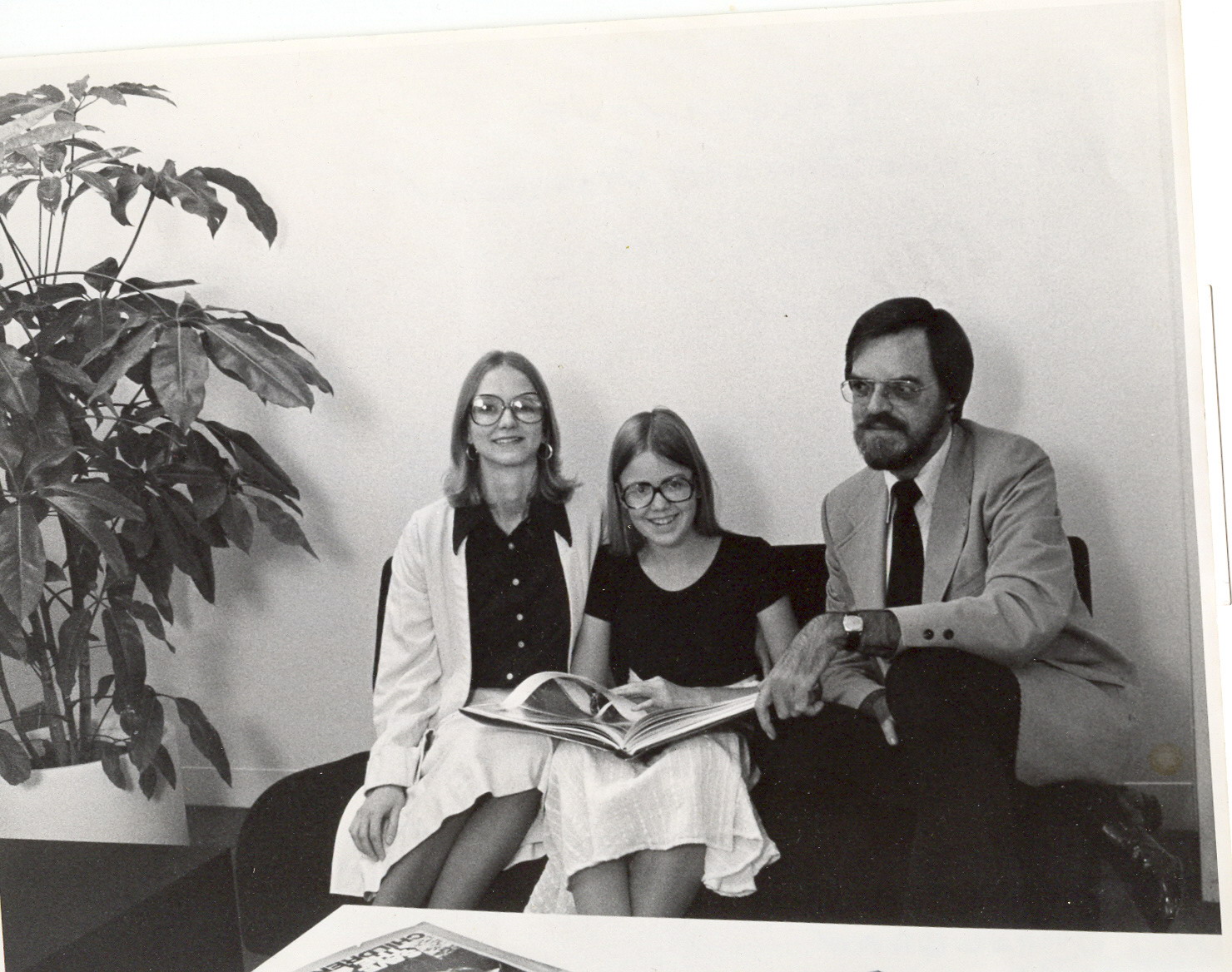

And October 25th is the birthday of Nancy, my ex-stepmother. She’ll be 54 this week – only ten years, one month, and three days older than I am. We even looked alike, with straight blonde hair and glasses, which used to confused people no end, especially because I referred to her proudly as my mother, when she barely looked old enough to be my sister. People would stare at us in shock and confusion. “She’s very well preserved for her age,” I would say haughtily.

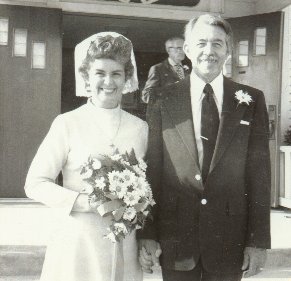

Nancy officially became my stepmother when she married my dad in 1974. The ceremony included a part for me: we all vowed that we would stay together as a family, forever and ever. You believe stuff like that when you’re a kid, especially when you’ve lost your original family, and desperately need to believe that families can be rebuilt.

In spite of her youth and her own problems, Nancy was a good mother to me, and some parts of my character today clearly came from her. She had raw courage, bordering on recklessness, which probably helped me out of my childhood shyness. She was young at the height of the hippie era, and imbibed to the full that period’s attitudes towards sex. “Open” marriage in the long run didn’t work out for most, but sexual liberation was a good thing, and I’m glad I grew up believing that sex was natural and fun and good, not something dirty or shameful. (It’s odd to consider that, had Nancy had her own child, say around 1975, her attitude might have been different by the time that child reached puberty: neo-conservatism came into vogue in the early ‘80s, and AIDS was hitting the headlines by 1986.)

Indirectly, Nancy taught me how to cook. Her parents, who had immigrated from Czechoslovakia after WWII, ran a restaurant on Pittsburgh’s South Side, and Nancy, having learned from them, was an amazing cook. I never actually helped out in the kitchen (I don’t remember if she never asked or I never offered), but I sat on the counter and watched her for hours. She never consulted a cookbook; she just knew what went together, and somehow, by watching her, I learned as well.

Far less willingly, I also learned to clean house. I had my chores (washing dishes especially), but Nancy was a housecleaning fanatic. During one mercifully brief period when my father lost his job and Nancy had to work full-time at a delicatessen, it was my job to clean the house when I came home from school – this included vacuuming EVERY DAY. I still remember part of the instructions she wrote out for me: “Start dusting from the top and work your way down. If I have to explain why, I can’t teach you anything.”

Nancy trained as an English teacher, but I don’t remember her ever actually teaching after her teacher training. When we moved to Bangladesh in 1976, where my dad worked for Save the Children, she reinvented herself as a specialist in “appropriate technology,” and was able to continue working in that field in Thailand and Indonesia, following (and later leading) my dad’s job changes.

I last saw Nancy in early 1985, in my own apartment in Austin where she and my dad had come to visit and supposedly make a last-ditch effort to put their marriage back together. Yes, it was real fun having that going on in my house. And it didn’t work. Nancy left, and that was the last I ever saw of her, though at the time I had no inkling that that would be the case. Our relationship was already strained; she had withdrawn from me as she had withdrawn from my father.

Nancy went on to do a nine-month master’s in international development at the School for International Training in Vermont. I got a few brief, strange letters from her during this period, while I was on my own study abroad year in Benares.

By the time I was leaving Benares, she was working for the UN High Commission for Refugees in Peshawar, Pakistan. There was a grim irony in this: her parents had hated my father for taking her away to all those “dangerous” places (Bangladesh, Thailand and Indonesia). But it was Nancy who chose – entirely on her own – to go to Peshawar, then and now one of the most dangerous places on earth! (It was probably al Qaeda HQ back then, before anyone had ever heard of al Qaeda, and there were almost daily bombs in the marketplace.) I offered to visit her there on my way out of India, but she said it was too dangerous.

I never spoke to her again, either. My dad referred gossip from the international grapevine that she had married a Turk who was high up in the UNHCR, and possibly had converted to Islam (her parents – devout Catholics – would have loved that!). Once when I was visiting Enrico in New Haven I got a garbled phone message from my dad saying that Nancy was in Pittsburgh and I could call at so-and-so number. I was thrilled, thinking this meant that she had actually been looking for me. I called. Nancy’s dad answered and, clearly lying through his teeth, claimed that Nancy was not there and had not even visited recently. “Well,” I said brokenly, “whenever you hear from her, tell her I called.”

I assumed that Nancy’s new husband might not know she had previously been married and had a stepchild, or that at least she might not like to rub his nose in it. But I couldn’t understand why someone as brave as Nancy couldn’t find a way to communicate with me if she really wanted to.

Sometime in the mid-90s, Enrico, Rossella, and I visited Pittsburgh, on a whim – I hadn’t been there in years, and remembered the city fondly. We had dinner with old family friends who happened to live only a couple of blocks from the house where Nancy’s parents had retired.

“What do you hear from Nancy?” Roz asked me.

“I don’t hear from her. I haven’t heard from her in years,” I said.

“Well, that’s odd. She comes on home leave about once a year to visit her parents, and always drops by for tea with us. And she speaks very fondly of you.”

I must have gone white with shock. I felt as though someone had punched me in the stomach. I stumbled through the rest of the meal and conversation, then, when we went back to our hotel, I sat in the bathtub and cried. I was trying to run the water hard enough so that Rossella (then about five years old) wouldn’t hear me and get scared, but she heard, and was frightened and utterly bewildered as to what could have upset me so much. I couldn’t understand – and still can’t – how Nancy could remember me fondly and speak of me to others, but would not speak TO me.

The next morning I looked up her sister’s number in the phone book and called. The phone was answered by one of Elaine’s teenage daughers (whom I had never met).

“May I speak to Elaine?” I asked

“Yes, I’ll get her. May I tell her who’s calling?”

“Deirdré.”

There was a pause and a whispered conversation on the other end, then the girl came back on. “She’s busy right now, can she call you later?” I gave her the hotel number, though I knew it was useless. Elaine never called.

Rumor has it that Nancy has been living in Geneva for quite some time now, where her Turkish husband works at UNHCR headquarters. Geneva is not far from Milan, and, even before the advent of Google, Nancy could easily have found me. But she never has. I have a recurring fantasy that I’ll run into her in an airport somewhere, sometime. If that ever happened, I don’t know whether I would hug her or punch her.