When you start losing parents, it’s natural and normal to contemplate your own mortality. For me, the death of my father, the great storyteller, meant not only that I am closer to my own death, but that I have lost parts of my history that I will never be able to recover, except via my own faulty and incomplete memories. (My mother, with whom I choose to have no contact now, declared in late 2007 that my brother and I had one year in which to ask her any questions about the past, after which she would never again discuss it. She responded angrily to the one question I did ask, so I did not learn much from her in that year.)

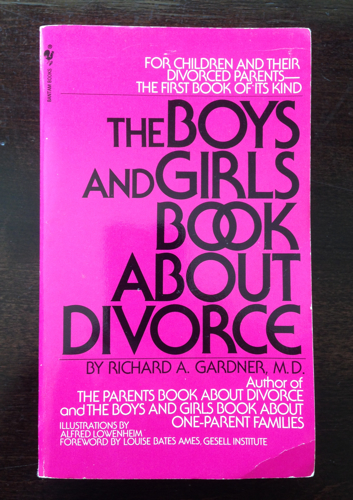

One way I can try to reconstruct my past is to revisit places and objects that are still available to me, such as The Boys’ and Girls’ Book About Divorce . It was the first book aimed at “those who are usually most affected by a family breakup: the 3,000,000 or more American children of divorced parents” (Time magazine). I think my dad gave me a copy soon after we arrived in Pittsburgh in 1972. I was the first kid I knew to have divorced parents, and I was desperate to understand my situation.

. It was the first book aimed at “those who are usually most affected by a family breakup: the 3,000,000 or more American children of divorced parents” (Time magazine). I think my dad gave me a copy soon after we arrived in Pittsburgh in 1972. I was the first kid I knew to have divorced parents, and I was desperate to understand my situation.

I hadn’t seen the divorce coming, let alone had any inkling what it would mean for me. I had known for some time that my parents were not happy together: they fought loudly and bitterly (behind closed doors, but I could hear them all over our large house), which frightened me and made me angry. But, growing up in a small community of expatriates in Bangkok, I may not have understood that it was even possible for one’s family to be blown apart in this way.

Sometime in 1972, I was told that my family was “returning” to the US, a homeland I remembered only from a Christmas visit two years earlier (we had been living in Thailand for the half of my life that I could remember). My dad would be going to grad school in Pittsburgh. Dad’s and Mom’s relatives mostly lived in Louisiana and Texas; we would have no family nearby to ease re-entry. Not that I knew my extended family very well: they, too, were familiar only from that one visit and a few, dim earlier memories.

We packed up our possessions in 55-gallon drums for shipping by sea, except for the armful of stuffed animals I insisted on carrying on the plane with me. The house with its lush tropical garden, beloved pets, servants who were part of the family, my school and my few friends: all would be left behind forever.

My parents had told me that my mother was staying behind to deal with some paperwork, and would follow later, with my infant brother. I was therefore puzzled that she cried upon saying goodbye to me at the airport. If she was sad, I assumed that I should be, too, so I cried along with her. But soon I was thrilled to be off on an adventure with my dad, including stopovers in Tokyo and Honolulu en route back to the US.

We eventually made our way to my aunt’s mobile home outside Coupland, Texas. I was happy to spend time in the country with my cousin, who had lots of animals to play with, and even horses to ride!

I can’t remember whether the letter from my mother was addressed to me or to my father. Whether I read it myself or someone read it to me or told me its contents. However it was conveyed, it was in Aunt Rosie’s home that I finally learned the truth. I remember focusing intently, dizzily on Rosie’s white curtains while someone explained to me that my parents were divorcing, and my mother would not be joining us: she was staying in Bangkok, and my brother Ian with her.

So I came to understand that I had lost everything I had known about my life – except my father – in one fell swoop.

As fas as I could tell at the time, this book did not help much.

Dr. Richard A. Gardner, a psychiatrist specializing in children, started his book by explaining the phrase Hobson’s Choice, and applying it to marriage: sometimes all you’re left with is the choice between an unhappy marriage, or no marriage at all. This made sense to me, but I was baffled by Dr. Gardner’s statement that: “Many children keep trying to get their parents to marry one another again.” My parents were living half a world apart, and already in new relationships. As a practical matter, I could not imagine how they might be brought together again, nor could I imagine them being happy together when I knew very well how unhappy they had been before. So I didn’t waste any pining on that scenario.

The book largely dealt with the then-standard American pattern for divorce, in which Mother stayed in the family home with the children, while Father lived somewhere nearby and saw the kids on weekends.

This was very different from my situation: my brother and I were separated, he staying with my mother in Bangkok while I was with my dad in Pittsburgh. I did not see my mother for a year, then she visited us once. I don’t remember much about this visit. I did not see her again until I was 18, in part because, during those years, both she and my father remarried and moved several times to several different countries. Most of my contact with Mom was via letters, and, even on paper, our relationship was rocky.

Though it did not fit my unusual story, Dr. Gardner’s book was somehow comforting. Years after I had left it behind, I remembered that it contained cartoon drawings of kids and their parents in various scenarios and moods – happy, sad, frightened, angry – accompanied by text saying that all these feelings were natural and ok to have, my feelings didn’t make me a bad person, and none of what had happened was my fault.

One thing kids hear a lot when their parents are divorcing (both then and now) is: “Mommy and Daddy both love you and will always love you, even if they no longer love each other, even if one of them has to go away.” Dr. Gardner took some heat, back in the day, for being honest with kids about the fact that, sometimes, a parent actually does not love you all that much. And, while that hurts, it’s not your fault: “…If a parent doesn’t love you, it does not mean that you are not good enough to be loved or that you are very bad or that no one will ever be able to love you… start trying to get love and friendship from other people.”

Even though I did not consciously remember this advice, I applied it. Whoever’s fault it was that I did not see my mother for so long and do not get on with her now (she blames my father), I went on to find allomothers throughout my childhood and youth, some of whom remained in my life well into adulthood. They (plus years of therapy) helped me survive and recover from the many losses that I have endured, as well as adding much to my life in their own right.

In retrospect, I probably have Dr. Gardner to thank for my instinct to move on and find substitutes for my mother’s presence and love. So: a belated thank you, Dr. Gardner. Your book helped after all.