We had a tremendously fun day yesterday. Thanks to Tom Alter, the Woodstock alum I mentioned a while ago, we got to hang out at the Grand Hotel in Locarno, Switzerland, where an Indian film is being shot. It’s a complicated thriller called “Asambhav” (“Impossible”) involving several gangs of malefactors plotting to kidnap India’s president. Of course there’s a resourceful and daring Indian secret service agent to step in and save the day, and a former Miss World to fall in love with him and help him beat the baddies (one of whom is played by Tom).

The hero is drop-dead gorgeous Arjun Rampal, a supermodel-turned-actor who happens to be a graduate of Kodaikanal, Woodstock’s sister institution in south India. He’s a thoroughly nice guy, whose ego seems not to be inflated by the fact that he’s a heart-throb to zillions of Indian girls (many of whom have websites dedicated to him).

I liked Arjun, but was thrilled to meet Naseeruddin Shah, one of India’s finest actors, familiar from my university days. Our Hindi professor used to show us films, mostly depressing ones such as “Aakrosh,” about a mute sharecropper whose wife is raped by a landowner. Naseer played a young lawyer trying (and ultimately failing) to achieve justice. More recently, Naseer is familiar to western audiences as the father in Mira Nair’s Monsoon Wedding, and about to become more so as Captain Nemo in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen.

Why Locarno? Tom told me that the Swiss government very actively promotes and supports Indian filmmaking in Switzerland. Indian filmmakers love the locations (yes, India has plenty of mountains, but they are far less accessible than Swiss ones), and bring business to the area (e.g., some technicians and equipment are hired locally, and one of the stuntmen is a bouncer at a local disco). The cast and crew, about fifty people, have taken over the Grand Hotel, a lovely old relic of a bygone era, soon to be consigned to some ignoble fate (possibly as a casino). To keep costs down, the team brought their own cooks from India, so we had an excellent Indian lunch and an endless supply of chai(Indian tea: tea, milk, and sugar are boiled together).

We got to watch a bit of filming, a single shot in which Naseer runs down a staircase, stops at the bottom, and shoots the guy following him, who falls theatrically, if unrealistically, over the bannister. This was maybe ten seconds of film, but it took four hours and dozens of people to set it up. Tracks were laid for the main camera to dolly along. Lighting had to be set up just so. Mattresses were laid to fall on. The stuntman was wired with a blood packet, detonated remotely by a gunshot technician whose partner handled the guns and made them go bang. The stuntman repeatedly practiced running down the stairs and getting shot, but stopped short of actually falling over the railing.

No one minded us tourists standing around, though director Rajiv Rai was worried that Rossella might be scared by the noise of gunfire. Not a chance. She was too busy soaking it all in, with an eye to her own future career in film.

Finally everything was ready. Down runs the man in the black mask (Naseer), followed by a pudgy bad guy (or was he padded?). Exchange of gunfire (not that loud, really, in spite of the enclosed space), blood appears, pudgy guy finally pitches forward over the railing onto the mattresses. End of take. Applause. Then everyone began setting up for the next shot, at the other end of the hallway.

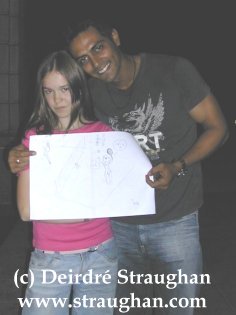

We decided to go for dinner rather than wait another four hours to see the next shot. The restaurant had paper placemats, so Rossella drew her impressions of the day’s events, including Arjun getting beaten at tennis by the local top player (an attractive young woman). When we got back to the hotel, Ross hid while we presented this to Arjun, who chased her down, pretending to be angry, but insisted on keeping the cartoon.