updated Oct 18, 2006 – prices could well be out of date by now!

The Milan metro is moving to a smart card system for local passengers with monthly or annual passes. This is fine for the locals, but the authorities, in their infinite wisdom, have also removed the old ticket machines from most metro stations. The new orange machines can only be used for smart card refills, and to buy single tickets for INTRA-urban (within city) trips – which, unfortunately, leaves out the new fair/expo complex at Rho. Most of the machines to stamp paper tickets at the turnstiles have also been replaced by smart card readers.

For Business Travellers to Rho/Fiera

The new regime has created a problem, particularly at Milan’s Central Station where many business travellers arrive. You can buy paper tickets from the big edicola (newsstand) in the middle of the mezzanine floor in the metro station (and maybe in the edicole in the railway station itself).

The prices for Rho are:

- 2 euros – single trip

- 5.50 euros – 24 hours’ unlimited use

- 9.70 euros – pass good for a week

During big expos, the edicola in the metro has three ticket windows operating, but there can still be very long lines.

If you walk around the corner to the right of the edicola, you will find a few of the old ticket machines which still sell all kinds of tickets – when they work, and IF you can figure out (in Italian) how to use them (the options seem immensely complex). These machines issue old-fashioned paper tickets which must be stamped in one of the few remaining ticket stampers – look for the little yellow boxes perched on top of the turnstiles nearest to the operator booth in the center of the concourse.

During fair times I also see people lined up at the new orange machines. I don’t know what happens if you buy one of the new intra-urban tickets and then travel all the way to Rho. In any case, if you buy one of these tickets, you slide it into the little slot on the front of the turnstile.

Your best bet is to try to get tickets BEFORE you get to Milan’s Central Station; many other newstands and tabaccai (tobacco shops) supply them – be sure to specify that you’re going to the fiera [FYAIR-ah] in Rho.

If you are staying out of town and commuting into Milan, it is often possible to buy Milan metro tickets at outlying railway stations; ask in the edicola at the station.

Getting to the Fair

Once you’ve got your ticket, go through the turnstiles to the left of the information booth. Immediately after you’ll see a staircase going down on your right. This takes you to the green line (Linea 2) of the metro going in the direction of Abbiategrasso.

Take this line five stops to Cadorna.

Change to the red line (Linea 1) in the direction of Rho/Fiera (obviously), which is the end of the line, so you can’t miss your stop.

See below for instructions on finding the right platform and train.

For Travelers Within Milan City

If you’re going to be using Milan’s public transit system (metro and/or buses and/or trams) more than three times on a given day, buy a day pass (3 euros, last time I looked). If you’re going to be using the system for multiple days but only twice a day, you can buy a ten-ride ticket from the orange machines.

Single and multiple tickets are good for 75 minutes throughout the system – run the ticket through the machine the first time you get on a bus or tram AND the first time you go into the metro. The ticket is good throughout the metro system as long as you stay underground (don’t pass the turnstiles), but once you have exited the metro you’ll need to use another ticket to re-enter, even if your original ticket still has time on it. However, you can keep riding on the buses and trams until your time’s up.

Figuring Out Which Train to Take

There are three metro lines – red, green, and yellow, aka Linea 1, 2 and 3.

The red line runs from Sesto (aka Sesto San Giovanni, a suburb of Milan) – Primo Maggio in the north, through the city center (Duomo) and out of the city again to the west. It splits at Pagano, with one line going northwest to Rho/Fiera (the new expo) and the other southwest to Bisceglie. So, if you’re heading west past Pagano, make sure you choose the right train! The final destination of the next train will be shown on the lighted display above the platform as the train pulls in, and also on signs on the front and sides of the train itself.

The green line runs from Abbiategrasso, south of Milan, passing through the city center and the Central Station. Heading east, the line splits at Cascina Gobba and goes to either Cologno Nord or Gessate. If you will be going east past Cascina Gobba, make sure you choose the right train!

If you do make a mistake and board the wrong train, get off as soon as you realize it. If you haven’t passed the station where the line splits, you can simply wait on the same platform for a train going to the right place, which is usually (but not always!) the next train to come along. If you have passed the split, you’ll need to go back the way you came until the split, then take the correct train.

The yellow line runs from Maciachini in the north to San Donato in the south, with no splits.

The lines intersect as follows:

- red and green: at Loreto and Cadorna

- green and yellow: at Stazione Centrale

- red and yellow: at Duomo

You can change trains (using the same ticket) at any of these intersections.

How to Find the Right Train

As you enter the metro station, look for signs overhead pointing to the train in the direction you want to go, which will be identified by the name of the station at the end of the line.

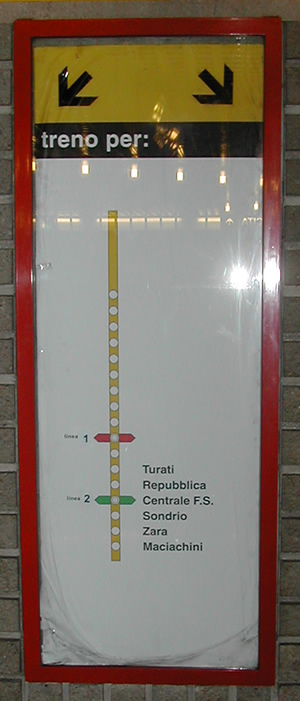

Then look for a sign like the one above. This example is a sign at the Montenapoleone station on the yellow line, showing the stops remaining in the northward direction to Maciachini. There are six stops remaining, and the yellow line will intersect with the green line at Centrale FS (the Central Station).

add your own Milan metro tips below!