Note: This is a heavily revised version of an article that I originally wrote around 2001, now updated for this year’s “significant” anniversary. 25 years online seems like a milestone worth marking!

I can say without hubris that I have a talent for communicating online. Which shouldn’t be surprising: I’ve been doing it for over 25 years.

Compuserve

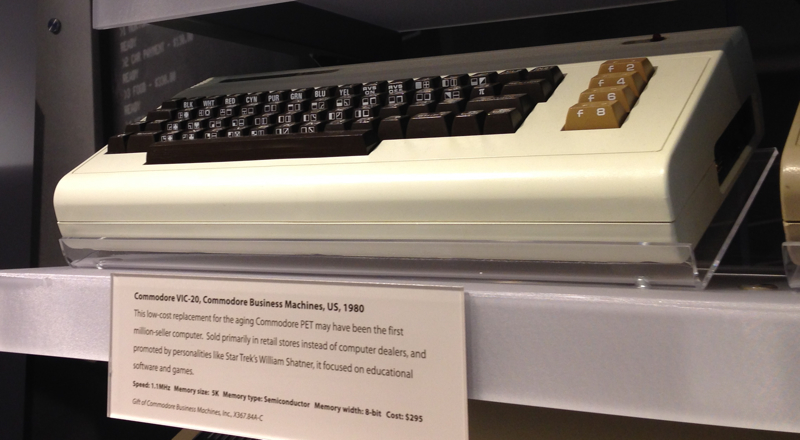

It began in January, 1982, while I was a student at the University of Texas. My father bought me my first computer, a Commodore Vic 20. For those who don’t remember, this was a computer built into a keyboard (you had to use a TV for a monitor). It had maybe 16 kilobytes of RAM, and there was no long-term memory; I remember perusing ads in early computer magazines for a “stringy floppy” – a way to use a cheap cassette recorder for long-term storage. Games and peripherals came in the form of hardware cartridges that plugged into the side of the unit.

My dad’s excuse for buying this thing was that I should learn computer programming, though the actual reason was that he wanted to play video games while convalescing from knee surgery in my living room.

Having already proven my complete lack of programming talent in a Pascal course my freshman year of college, I didn’t get far with programming the Vic 20: I could print my name to the monitor in different colors, and that was about it. I wasn’t very good at Space Invaders, either. But we had also bought a modem, and that was how I found out what computers are really for.

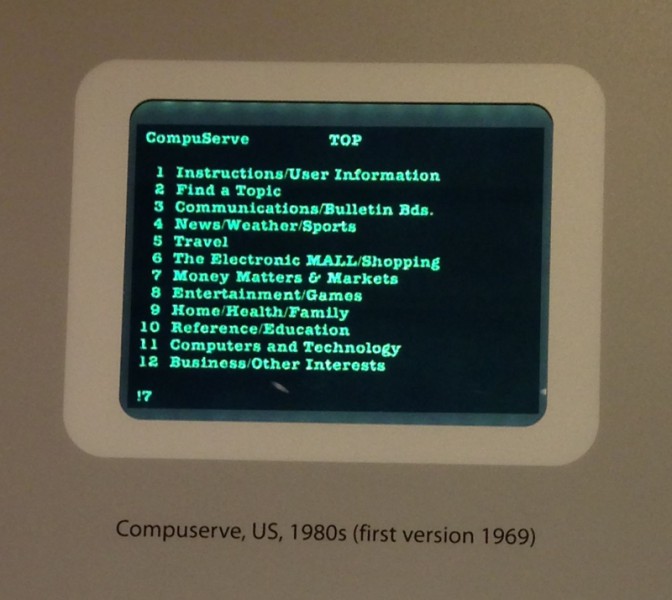

There must have been a coupon in the box, because I joined CompuServe, at that time the province of a few thousand elite geeks (though I guess we weren’t elite enough or geeky enough to have already discovered the joys of online via ARPANET).

And the first thing I found on CompuServe was the chat rooms. The analogy used for online chatting in those days was CB radio (anyone remember that?), so everyone was encouraged to use a “handle” instead of a real name.

I have said that I’m no good at programming. One thing I am good at is finding the bugs in other people’s programs. I somehow, inadvertently, managed to enter CompuServe’s chat rooms the first time via a back door. As I entered, the system asked for my name (instead of a handle). So I typed in my real name. By the time I realized my (or the system’s) mistake, my fate was sealed: everybody knew me as Deirdre’, and I have simply been myself online ever since.

(Just as well. I wouldn’t have known what alias to use anyway; I have spent so much of my life explaining how to spell and pronounce my name that I now cling to it stubbornly – accept no substitutes!)

I was immediately popular in the chats, because in those days men vastly outnumbered women, and I was young and single (and said so). One guy told me that he thought it was because Deirdre’ in print looks rather like “Desire”, and because I wrote well. An added advantage was that I could type fast!

It was all pioneer territory in those days, and there weren’t many of us, so we went to some trouble to get together in person. About a dozen met in Austin, then some of the same group, plus others, met in Dallas. True to our geekiness, our big activity during that trip was going to see Return of the Jedi, though we’d all already seen it at least once. (One of the guys was Filipino; he told us that at some points the Ewoks are speaking Tagalog: “Oh, what a beautiful golden thing!” they say upon seeing C3PO.) It was one of the CompuServe crowd who introduced me to the concept of fan fiction.

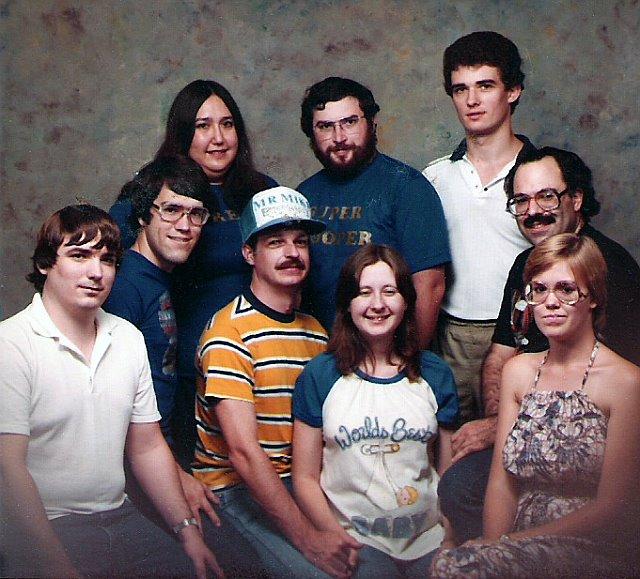

The photo at the top of this page, added Jan 6, 2008, shows the old CompuServe crowd, circa 1983. Photo passed on by Ken, from the site of Mike Stickles (in the orange striped shirt) who, sadly, passed away a few days ago. He was, among other things, a piece of Internet history: he and “Silver”, seated together center, were the first people to have met and married online.

Time magazine ran an article in 1984 titled: X-Rated: The Joys of CompuSex. Of course they had to emphasize all the sensational elements, and end on a sour note about a woman who “grew so addicted to CompuSex that her husband walked out.” The mainstream media today are still fond of studies “proving” that people who spend a lot of time online are lonely introverts who can’t deal with real life.

As for me, I didn’t have much time to get addicted. CompuServe cost $6 an hour, and after some months my dad got tired of paying the bills. Cheap/free local BBSs just weren’t good enough, so I was offline. But my online education had been well launched.

In 1984, while visiting my dad in Jakarta, Indonesia, I worked for six months in the Commerce section of the US Embassy there. I did various secretarial work on a Wang word processing system (I had previously learned word processing on a self-contained Philips terminal, and electronic typesetting on a machine the size of a refrigerator). The Wang was a centralized, mainframe-type system with terminals and tractor-feed printers that were always jamming.

Because all the terminals were linked to a central server, the Wang could be used to broadcast messages to every terminal in the embassy, or to send a message directly to anyone whose logon name you knew. The feature wasn’t obvious; I noticed it when an announcement was broadcast to us all. I wanted to use it to send messages to my friends, but couldn’t figure out how to originate a message. I asked the system administrator, who sniffily told me that messaging was not for use by plebeians like myself.

That wasn’t enough to deter a curious mind. The next time a broadcast came through, I noticed that the menu at the bottom of the message included reply options. One of those options got me into the message system. I could then send private messages to my friends: as long as we kept the system open by replying to each message, we could use it to originate new messages whenever we wanted. My first system hack!

The admin never noticed until one of my friends made a mistake. We had just returned from an island weekend with a bunch of Marines (don’t ask), and she tried to send me a mildly obscene message reminiscing about it. She hit the wrong menu choice, and broadcast her message to the entire Embassy. The first person to see it was the Ambassador, who was not amused.

I wasn’t online regularly again until 1993, when the book Fabrizio Caffarelli and I wrote together (“Publish Yourself on CD-ROM”) was published. It was one of the first books in the world published with a CD-ROM, which contained a demo version of Easy CD 1.0, and a screen-readable version of the book itself.

I had wanted to publish the electronic version of the book in Adobe’s new PDF format (which I’d heard about in the course of my work as a journalist for Italian computer magazines), but that wasn’t quite ready at the time. I used instead the same FrameMaker software I’d used to lay out the book, along with a hypertext reader supplied by Frame – I negotiated the rights to include this on our CD, which I believe was the first publication to use it. (That company is now owned by Adobe).

Designing the electronic version of the book was also a formative experience: I became adept at hypertext long before I saw the Web.

The book mentioned our CompuServe address and that we’d be glad to hear from readers. Hear from them we did, because the disc didn’t work! Something had gone wrong in manufacturing, and no one at Random House had thought to test the disc before binding it up with the book.

That was my first experience with online customer service. I was just sick over the whole situation, but Random House quickly had a working disc duplicated, and arranged shipping so that anyone who contacted them could get a replacement quickly. Once this fix was in place and easily obtainable, I was pleasantly surprised at how forgiving our readers were. In a way it was a bonus, because the mistake spurred people to get in touch with us who otherwise would never have bothered.

By then I was working full-time for Fabrizio at Incat Systems, writing software documentation. I spent time with customers on CompuServe, mostly because I enjoyed it, but I also suspected that it would become important someday. (I vividly remember sitting in the back of a bus on my way to work in Milan, reading a Seybold Report about the World Wide Web – the first I’d ever heard of it. That memory sticks oddly in my mind; even then, I guess, I sensed that the Web was going to be big in my life.)

My early online activities for Incat consisted in hanging out in the relevant CompuServe forums (I eventually started a section just for our software) and answering email.

The Internet

All my best ideas about supporting customers online came from the customers themselves. It was a customer who suggested that I get out on the Usenet to defend our products; that’s where I first met Dana Parker, another of the three “grandmothers of CD-R” (the third is Kathy Cochrane). Dana and I locked horns at first, and for a while I was convinced that she was a man – the only other Dana I’d known had been male.

When Incat was bought by Adaptec in 1995, I had already begun creating Web pages, in hopes that with the new company we’d be able to get them online. (I had been searching for a web host for Incat; one early provider told me frostily that our company was far too small to afford their services.) I had created 30 pages about CD-R technology and our software, using Microsoft Word’s then-minimal HTML capabilities, and what I already knew about hypertext.

I arranged a meeting to show my pages to the person then in charge of the Internet at Adaptec. I didn’t contradict her when she commented on the amount of work that must have gone into these pages, but then she said casually: “I understand that you also do other things for Incat?” Er, um, yeah… all of the software documentation, usability, and a lot of the marketing materials. She never forgave me for that.

It took six months after the acquisition to transition some of my activities to other departments at Adaptec, including the documentation I had been doing. I didn’t mind getting out of writing manuals; I’d been doing it long enough to be bored. But I had no idea what Adaptec intended to do with me, nor, apparently, did they. Somewhat randomly, they stuck me in marketing. I met my new boss, Dave Ulmer, in February of 1996.

I couldn’t have been luckier. I told Dave what I’d been doing online (CompuServe, Usenet, answering email, web pages) and he said: “Fine, do more of that.” And that’s about all the direction he ever gave me. He not only understood the Usenet, he was frequently and visibly out there himself.

The rest, as they say, is history.

Nov 16, 2013 – New photos added from yesterday’s visit to the Computer History Museum, which I highly recommend.

this post is now part of a series: Global Telecommunications: A Personal History