| Thanks to a tip from Ross, I have for some time been following a very funny fotolog by Francesco Rabaglia, aka Papa Fan (papa is Italian for pope, differentiated from papà – dad – by the stress). It’s hard to see the humor unless you understand Italian well: basically the writer is putting funny captions in heavily “Germanized” Italian on photos of Pope Benedict (also known in Italy as Papa Ratzi).

A few days ago he published an original poem, translated here with permission. Keep in mind that this is not quite normal Italian – there are no Ks in Italian, but they are often used in humor and comics to denote a German accent.

|

Category Archives: Woodstock School

Growing Up in Boarding School

Though Rossella is by and large a wonderful young woman and a joy to be around, she does have her teenage moments and attitudes. She doesn’t like to wake up in the morning, her floor is usually strewn with clothing, she is undisciplined about studying… I sometimes reflect ruefully on the fact that my parents missed out on many of the pains and joys of my adolescence: I spent it most of it away at Woodstock School.

The idea of sending your child away to school is anathema to many parents (and perfectly normal to others, depending on culture, class, and family history), but it can be a fun and useful experience for the teens themselves. They become self-regulating and independent because they simply have no choice. Many common teen habits cannot be tolerated at boarding school – some forms of behavior would simply be impossible to manage en masse.

You Gotta Get Up…

Living in a dorm means responding to bells: bells to wake up, bells to go to meals, bells for showers, bells for lights-out, bells for emergencies, and of course there are the school bells throughout the day. When the morning bell rings, you had better roll out of bed on your own, because there’s no mother there to keep coming back to nag you. If you persist in lying in bed, you’ll miss breakfast, and if you’re late for school, there are consequences. Needless to say, this is useful discipline for later working life.

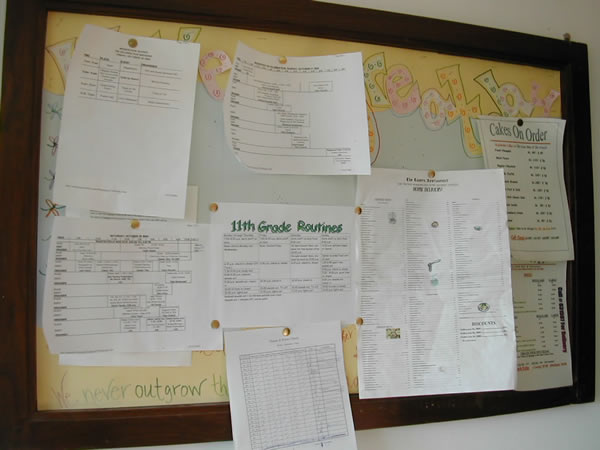

the routines of dorm life

Keep Your Room Tidy

When I was at Woodstock, dorm rooms were inspected once or twice weekly and, if we left them messy, we got demerits that could add up to gating (a punishment that meant not being allowed to leave the dorms for anything other than classes for weeks or months) or restricted to campus (no bazaar on Saturday!). Being thus forced to clean up after ourselves was good training for any teenager, especially those who had servants to do everything at home (as was common in Asia at the time).

(Tidiness doesn’t seem to be quite as enforced as it was in my day. At least they matched Ross with an equally messy roommate.)

Manage Your Money

My parents never had to argue with me about pocket money. We had a (very small) set allowance at school – I think the maximum allowed during my senior year was 100 rupees a month. This amount was equal for everybody, and there was (at least in theory) no way to beg parents for extra if we had spent it all before the end of the month. In that situation, you learn to spend carefully – another very useful life lesson.

Manage Your Studies

I suppose all boarding schools have specific times set aside for studying. At Woodstock in my day it was 1.5 or 2 hours after dinner, four nights a week – if I remember correctly, we had a shorter study hall on Wednesdays to allow time for a social activity afterwards. Any free periods during the school day were also designated as study halls, which you did in the library under supervision (it was a Senior priviledge to be allowed to study anywhere on campus).

If you were on the A or B honor roll (3.5 or 4.0 grade point average), you could do evening study hall in your room rather than in the dining hall. A teacher would come around once or twice to check that we were each in our own rooms, but otherwise it was up to us to use the time wisely.

Practicalities

Even if we weren’t used to having chores at home, we had to take care of some things at school ourselves, such as laundry. Not washing it ourselves, but bundling it up each week for the dhobi (washerman), with a checklist of how many of each item we were sending, then checking it in again and chasing down anything that was missing when the bundle came back. If we needed clean clothes next week, we knew to make sure they got into the wash this week. (Or, preferably, the week before – clothing takes a long time to dry in the monsoon.)

We had to take care of our clothes and our possessions, replace things that needed replacing, etc. – again, no mom around to notice that all your socks have holes in them and your t-shirts have all gone gray.

Communal Living

Living in a dormitory with 100+ other kids, well, you’d better learn to get along with people. For starters, we all had at least one roommate, and the rooms weren’t huge, so you had to respect others’ personal space, and learn to find privacy when you could. I tended to need a lot of time to myself, so most days I would go straight down to the dorms after school, when others were off doing sports etc., so I had at least my room to myself.

Survival Skills

Here I’m thinking mainly of food – an obsession of growing teens, the more so in any institutional cooking situation where the meals are… well, probably not like Mom makes. The downside is that you learn to eat fast, so that, if there is anything good on your plate, you can go back for seconds before stocks run out. You can often spot a boarding school survivor by this behavior: he or she is the one waiting impatiently for a post-dinner coffee while the rest of the party are still on their salads!

The upside is that, while you deeply appreciate good food, you’re not a fussy eater, and can survive on just about anything when you have to.

The Rules

Living with parents, teens are always testing boundaries: “Why do I have to be home at a certain time? What do you mean I’m too young to go to the disco?” This struggle for independence is an important part of teen development, but exhausting for parents, who receive conflicting advice from the entire world (“Be stricter! Be more understanding!”) and may not agree even between themselves on what’s to be done.

A boarding school has set rules that everyone knows and must live by. It’s clear why the rules need to exist, even when they are more restrictive than you might have at home: it’s far more difficult to keep track of several hundred teenagers than one or two.

At school, there’s not much leeway to argue about the rules, and the penalties for infractions are clearly stated and (usually) fairly applied. So it’s up to you, the student, to decide whether to risk breaking the rules, and you know exactly what to expect if you get caught. Boarding school in this way is a good introduction to adult life: you learn early that you are responsible for your actions.

The Results

A young person leaving boarding school for college is likely to be far more mature in many practical ways than his or her peers who come straight from home. One Woodstock classmate of mine said that he felt many of his college classmates wasted their first year simply getting accustomed to being on their own, whereas he was able to be productive from Day 1.

Last but not least, boarding school teaches us humility: instead of being Mom and Dad’s pampered darling, we each have to pull our own weight in the community – which includes aiding and comforting our peers when they need it. We learn to take care of those around us, and that it is natural and human and right to do so.

And that’s not a bad lesson to be starting life with.

Getting Girls Into Science Early

During my recent trip to Colorado, I stayed with Tin Tin Su, a Woodstock School classmate who is now an associate professor in Molecular Cellular Developmental Biology at the University of Colorado in Boulder.

Tin Tin is good at explaining what she does, and delights in sharing her knowledge with people of all ages. I was thrilled to be able to capture her giving a first lesson in fruit fly genetics to a highly intelligent – and highly interested – girl named Sasha. Tin Tin was thrilled, too: as a “sideline” she heads up a project at CU aimed at helping to equalize the number of men and women in sciences. Showing girls from a very early age that science is a cool and fun career – she considers that part of her mandate.

Our Lady of Drosophila

Jul 15, 2007

Tin Tin is also a painter. A few years ago she made a painting as a gift for her lab, which she explains in this video.

Woodstock School Questions & Answers

If you search Google for Woodstock School, one of the top results you find is my site. This means that I’ve become an unofficial source of information on the school and what it’s really like to go there.

Back in February, I was delighted to receive email from a prospective student, who wrote: “I recently came across a study abroad program called SAGE. They send students to the Woodstock school for a semester or year, and I am extremely interested. I found your site and read your pages about Woodstock. It sounded like a great experience! I was wondering if I could ask you a few questions about it because I am beginning the application process and would like to hear more about the school from alumni and current students.”

She then asked a list of questions, which she has graciously given me permission to publish, along with the answers I sent to her.

1. What was the best aspect of Woodstock?

The people, both staff and students. We had our teenage falling outs etc., but mostly everyone got along even back then, and now we are all each other’s best friends, in spite of (because of?) a wide variety of backgrounds, experiences, lifestyles, and opinions.

I am class secretary for my class and have kept in close touch with most of them over the years, but also with lots of other Woodstockers. For example, Nathan [Scott, head of the SAGE Program] is the younger brother of my classmate Chris, and Nathan and his wife spent part of their honeymoon at our home in Italy. Woodstock relationships last, and that’s been very important to me.

These contacts are also of practical use in later life. At various points in my career I have found jobs for WS’ers, and yesterday a WS alumnus whom I met after we’d both been in Milan for many years took me to lunch to offer me work!

2. What could have been better?

The food! It was legendarily bad in our day and we were always hungry. I’ve been back on quite a few visits in recent years and can testify that it is much improved. Although we’re still talking about a remote place in India where you don’t always find the ingredients you might want… I’m told the students still complain. ; ) That’s why everyone goes to the bazaar on Saturday to eat.

3. What was the most valuable lesson you learned while at Woodstock?

Hard to say – I learned so much in so many ways. I guess it would be something to do with getting along and working and living with all kinds of people.

4. Why do you think diversity is important for a school setting and how did it help you learn?

Even if you’re fortunate enough to go to a school where they try to teach you about world cultures, religions, etc., you’re never going to really get it until you’ve been living and interacting daily with people profoundly different from yourself. And it’s especially valuable to do this while you’re young. Woodstockers understand right down to their bones that someone can think and believe and act differently than they do, and still be a good person with basically the same motivations as themselves. I think that’s a foundation of real understanding, and a place from which to negotiate our differences. I truly believe that, if there were more schools like Woodstock, there would be less war in the world.

5. What were the teachers like? Were they easy to understand?

In our day they were a mix of Americans, Brits, New Zealanders, Canadians, Indians, and probably more that I don’t now remember. They were mostly very good teachers. They certainly prepared us well – after Woodstock, college seemed pretty easy!

Another advantage of WS is that class sizes are small, so every student gets a lot of teacher attention. And you’re living in a small environment with the staff as well as students, so you are in constant contact with them. Staff are involved in all sorts of activities besides teaching – chaperoning hikes and trips, supervising study halls in the dorms, some play in the band and orchestra and sing in the choir, etc.

It takes a special kind of person to want to go live in a remote corner of India to teach international students. They tend to be more dedicated teachers, and truly interested in being involved in their students’ lives. Any Woodstocker will tell stories of specific staff members whom they remember fondly. I’m still in close touch with several of my favorite WS teachers.

6. Did Woodstock prepare you for the future well?

Yes, though I use what I learned in my extra-curriculars more than what I learned in classes. I was on the newspaper and yearbook staffs, and in student government, and I tended to be called upon for public works art projects (“The elementary school looks a bit drab – why don’t you do 12 enormous batiks to brighten it up?” “We need an ass’s head for Midsummer Night’s Dream…”).

Because there are relatively few students, everyone has a chance to get into everything. My roommate was captain of the basketball team and the cheerleaders (we weren’t very serious about cheerleading – a bunch of girls just decided they wanted to do it, so they did it. However, that meant that only the boys had any cheering since the same girls played on all the girls’ teams!). My roommate was also in band, orchestra and choir, and we worked on the yearbook together. There were also opportunities for volunteer work, which is even more strongly encouraged today.

And then there was the environment we were in – lots of India to explore even within the immediate area.

So WS taught us to be true all-rounders. The result for me has been a career marked by flexibility and quick adaptation to whatever situation I found myself in. And I have no fear at all of plunging in and learning new things as I need them, which is a key requirement in today’s working world. Woodstock (or any other school) could not have prepared me specifically for my career – the things I do now were undreamt-of in 1981. But my preparation at WS gave me confidence that I can learn anything I need to, and invent the things that no one else knows how to do yet.

I also learned to write well at Woodstock, and that’s a skill that will always be important in almost any kind of work.

7. On a scale from 1 to 10, how difficult were the classes?

I don’t know what to compare them with. I was a lazy student, and worked to keep my average above B only because that let me spend the compulsory evening study hall period in my dorm room instead of the dining hall. Some things like English and History I did well in without much effort, sciences were harder for me.

If it helps for comparison, I can say that I did very well on PSATs and SATs. And, as I said, I found university fairly easy after Woodstock. So I guess WS classes were fairly rigorous, though they didn’t seem that way to me at the time. On the other hand, the nephew of one of my classmates attended WS briefly last fall (he returned home to the US for family reasons after only a few months), and said he found WS easier than his school in northern California. Which surprised me. He might have found that it got harder as the year went on.

Why Send My Child to Woodstock School?

Someone who has never attended Woodstock School may legitimately wonder why anyone would wish to send their child there.

I went to Woodstock in 1977 because I had no better educational choice (except to continue with correspondence school in Bangladesh, where my parents were living and working – a year of which had already been more than enough). “No other choice” was the case for many Woodstock students in those days, when jobs in development, missions, or international business were more likely to send Westerners overseas, and there were fewer international schools in odd places around the world for their kids to attend.

Woodstock nowadays is one of Asia’s elite schools, preparing students for still-much-desired admission to universities in the US and UK (as well as Asia’s own top universities). But it’s not so obvious why any student should come from outside of Asia. And there are plenty of reasons not to. Let’s look at some of those first.

(Some of) The Reasons Against

It’s Boarding School

Woodstock is a boarding school, a concept foreign to American and most European culture: if you love your child, how can you bear to send him/her away? In Italy, boarding school is widely considered something that parents do with children whom they cannot control at home, and/or it’s thought to show a lack of proper parental feeling. (Although we have several Italian friends who went to boarding schools in Italy and elsewhere and loved it: the negative attitude seems to come from Italians who have no actual experience of boarding.)

It’s in India!

Secondly, Woodstock is in India, specifically in the small town of Mussoorie, 7000 feet up in the foothills of the Himalayas. A location which, much as I love it, is what the foreign service used to call a “hardship post”. It’s cold and wet during the monsoon, cold and sometimes snowy during the winter (though fall and spring are gorgeous and not too hot).

School facilities and infrastructure are enormously, unrecognizably improved since I attended 25 years ago, but most of the buildings are still old and unheated, many cannot be reached except on foot, and the overall level of comfort is well below what we in “the West” are accustomed to.

Physical discomforts are bearable, perhaps even character-building, but there are worse potential dangers. Health is a concern: it’s a lot easier to get catastrophically sick in India, and a near-certainty that at least some “Delhi belly” will befall any traveller there (although, during our 2005 trip to India, I got sick and Ross did not. My own fault – I should not have had that lassi in Jaipur…)

On the other hand, India has very good health care these days – so good that people are travelling from the US, Canada, and UK to have non-urgent surgery and other treatment far more cheaply in Indian hospitals than they could at home (“medical tourism” they call it, and it’s a booming business).

…and there are plenty more aspects of India that the average Western parent inexperienced with Asia will find frightening, bizarre, and incomprehensible. But let’s not dwell on them for the moment.

The Reasons For

It’s a Nurturing Environment

At a Woodstock reunion long ago I talked with an older alumnus whose own children were then college age.

“How come your kids never went to Woodstock?” I asked him.

He explained that his daughter had done very well at home in Canada, was well-adjusted, made good grades, had lots of friends, etc. He had never even considered sending her to Woodstock, because there was no reason to take her out of her happy situation.

His son, on the other hand, had had both social and academic problems at school, and didn’t seem to be going anywhere with his life after high school. The alumnus thought his son might well have benefited from Woodstock, as a total change of scene if nothing else, but his wife would not hear of it: the idea of sending her son off to school in India was just too strange and scary. The alum regretted that they hadn’t tried it.

I’ve spoken with many alumni who feel that they benefitted enormously from Woodstock, even if they were there only a year or a semester. One of my own classmates came for her senior year, having done all the rest of her schooling in a standard US high school, where she was considered something of a weirdo. She credits Woodstock with making her feel that she was fine just the way she was, giving a huge boost to her self-confidence. (Years later, my own daughter said the same.)

For me, Woodstock had a tremendously positive impact on my life, as I have written before: “The four years I spent there nurtured me, gave me self-confidence, and helped to heal the wounds of my parents’ divorce and other upheavals. Years later, my therapist told me that if I hadn’t gone to Woodstock, I would probably have ended up ‘gibbering in a corner somewhere.'”

Do you have to be among the walking (psychologically) wounded for Woodstock to do you good? Of course not. Plenty of healthy, well-adjusted kids have gone there and enjoyed it. The Woodstock environment is nourishing and nurturing for just about everyone. How and why it is this way is a topic for a much longer article!

It’s in India!

At a reunion in London in 2003, I met the parents of a German boy who had just gone to Woodstock for his junior year abroad. The parents had travelled to London to meet alumni because they knew very little about the school or the people it produced. How on earth did their son end up there?

He had been doing well in school in Germany, but was not satisfied with the level of English he was learning. (I assume that his father, an international businessman, had drilled into him how important it is in today’s global world to speak good English.) So the boy wanted to go to a school where he could study in English, but exchange programs in the US or Canada did not appeal to him (possibly for the same reason – no choice of the actual school – that similar exchange programs from Italy did not appeal to Rossella).

His father, whose business took him frequently to China, suggested that he look for a school in Asia: “Asia is the future,” he told his son.

The boy did a search online, and came up with Woodstock. His father stopped by for half a day on one of his China trips, approved of what he saw, and off the boy went. I believe he stayed there a second year as well, and graduated with his class.

Unusual? Certainly. Weird? Maybe. But the father had a point. The Economist recently stated that “India may overtake Germany as the world’s fifth-biggest consumer market by 2025.” The future, indeed.

Indian culture is already felt throughout the world. In a recent episode of the American TV show Heroes, the Indian character used the word goondas without explaining it, clearly expecting both the character he was speaking to and the audience to understand it (the meaning was clear enough from the context: goondas are thugs – and thug is also originally an Indian word). Anyone who wishes to be successful in an increasingly globalized and Indianized world will certainly benefit from knowing India well! (China, too, but I don’t know of any Woodstock-like schools there. Maybe Woodstock should offer courses in Chinese language and culture.)

Enduring Friendships

Many alumni and former staff gathered in Mussoorie to celebrate Woodstock’s 150th anniversary in 2004, some bringing family. My classmate Deepu’s daughter said to her afterwards: “I see you with all your old friends and hear the great stories you tell. When I’m old, I want to have stories like that, too.” She has now been at Woodstock for several years herself, and presumably has her own friends, and stories to tell with them.