My father-in-law, Mauro, died last week. Although he was 78 years old and unwell in several ways, his death was very sudden and unexpected, and may have been due to medical malpractice. As you can imagine, this possibility makes the event all the more horrifying.

Naturally, this is a time of pain and mourning for all of my husband’s family, myself included. I’ve known Mauro for 17 years. You can’t know and love someone for that long without feeling a gap when they go.

Still, long before the first shock had worn off, a part of my brain was standing back and observing, with the eyes of an anthropologist, some Italian customs that I have not previously had a chance to see close up, those related to death and mourning. Even when I’m in pain, my curiosity never deserts me – this is one of my survival mechanisms. Mauro, who never lost his own boundless curiosity about everything in the world, would approve.

So, how does death work in Italy? I should first note that I don’t have much experience with death anywhere. One of the side-effects of boarding school is that you spend most of your time with your peers and relatively young teachers, and have less exposure to ageing grandparents and their deaths (or the births of younger siblings, for that matter). The only other funeral I’ve attended so far was of my dad’s friend Harry, back when I was in college. I wasn’t at all sure what to expect in Italy.

In the US, it seems to be common during times of grief for neighbors to show up with food. So, in Abruzzo, I was amused when a neighbor delivered a watermelon. A few days later, this same lady brought over a timballo (the Abruzzese version of lasagne), which was wonderful. But by and large we were on our own for shopping and cooking (mostly handled by my brother-in-law, an inspired cook at all times – yes, even better than I am).

The direct practicalities were handled by a funeral agency, recommended by the neighbors as neither too cheap nor too grasping. What a peculiar profession to be in. Though I’ve only seen one episode of Six Feet Under, I can see what fertile grounds for a TV show the funeral industry must be. At least these guys weren’t smarmy; they were wearing street clothing, and their attitude was kind and respectful. The small agency office contained ten different models of coffins, mounted in racks on one wall. The other side of the room had display cases with samples of the various accoutrements you could add to a gravesite – lights, vases, photo frames, and statuettes of Padre Pio.

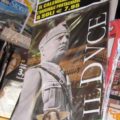

One of our first steps was to oversee the wording of the funeral posters. I have seen these everywhere in Italy, and always wondered about them – it seemed undignified to me, plastering announcements of a death all over town like election posters. (Although the death announcements often occupy specific billboards reserved for them, they are also stuck up on just about every flat surface, including electrical/phone switch boxes and the like.) But it’s the “done thing,” and we were doing all the done things.

These posters use stock phrases. Ours started with Si e’ spento serenamente oggi… which translates literally as “S/he has serenely gone out [like a candle] today…” We deleted serenamente. Then came the name and the age and “This announcement by…” – we wanted to add “sad” in front of “announcement,” but were told that this is no longer the custom – “…the wife [name], the sons [names], and all the family members.” (Even were it customary, I would not have had my name on there – it’s just too unfathomable to most people.) Then the date of the announcement and the date, time, and place of the funeral.

They told us that the posters (“We have a permit for 25 posters per person”) would go up very shortly. In fact, within an hour we had a call from someone who had clearly got the news via the posters, although we were also getting calls from all over Italy as word spread. The posters served to alert local people to the event, so that they could come to the funeral. In Mauro’s case, there were also two articles in regional newspapers.

That was Wednesday. On Thursday, a stack of telegrams arrived. Now I know why the telegraph service, otherwise never used, still exists in Italy. Even the downstairs neighbors sent telegrams. You may wonder: couldn’t they have left a card outside the door? The greeting card industry in Italy never got off the ground (which may be the fault of the postal service!), so condolence cards may simply not exist here. Telegrams are the done thing. Many of them were very long, for telegrams, with glowing tributes from university and editorial colleagues; some were formulaic condolences from local business owners, etc.

The phone rang constantly, forcing Enrico and his mother to repeat the story over and over. But perhaps that helped, as a sort of catharsis, as did the many personal visits from old friends and colleagues.

The funeral was finally held on Sunday evening. We followed the hearse to the church in our cars and, as we arrived, it started pouring rain. We waited a few minutes, but the rain clearly had no intention of even slowing. So I took off my shoes (run up marble steps in the rain in high heels? That’s just asking to add farce to tragedy) and sprinted into the church, to confounded stares from the dozen or so people gathered around at the door. I was soaked anyway, by the time I got inside.

The pall bearers (hired by the funeral agency) tried to wait out the rain for 20 minutes or so, but finally gave up and got wet. The coffin (closed, by our choice, though traditionally it would be open) was carried up the aisle and laid on cushions on the floor at the top of the aisle. It was draped with a “cushion” of flowers with a banner saying “from the wife and children”, and a bouquet from someone else was leaned on the front of the coffin. Other flower arrangements were placed on the steps leading up to the altar.

Although he didn’t know Mauro personally, the priest had not called the family for help in preparing the ceremony, so I was relieved to find that he had been talking to other people, at least. Still, I wasn’t impressed. He did the standard Sunday mass, not even a funeral mass (so I was informed by one of the cousins – I wouldn’t have known the difference), and the text of the sermon was Luke 12:35-38, the parable of the watchful servants. Which had precisely nothing to say on the present occasion; the priest himself admitted as much, and said it was the standard liturgical text for the day. Lazy! Even I, who was forcibly spoon-fed what little I know of Christianity, could have chosen a better text. [I later learned that, because the funeral was held on Sunday, he had no choice but to do a standard mass following that week’s liturgy. Don’t get me started on the institutional rigidity of the Catholic church…]

I also did not find in the least bit comforting all the stuff about how “he is now face to face with God.” It’s doubtful that Mauro himself believed that, though he was a great respecter of traditions; none of the rest of us did.

Fortunately, there is also a tradition at Italian funerals for anyone who wishes to speak after the mass is completed. The first was the mayor of Roseto, who did not take political advantage of his platform, but gave a kind and moving speech about Mauro. A colleague and then a former student (and long-time friend) followed; the latter was careful to mention that Graziella was Mauro’s professional colleague and collaborator as well as his wife. The last speaker was a poet with whom Mauro had collaborated on a book, who had known him only from that recent experience, but had some very graceful things to say. On the whole, it was satisfying that the funeral ended with remarks about Mauro himself and the real impact he had on many people’s lives, rather than the woolly stuff about “where he is now.”

The coffin was carried back out to the hearse, while the family stood and received condolences from everybody. I was kissing people I didn’t even know. I don’t know whether it’s the done thing, but I minded my American manners, and thanked the speakers for their kindness and appropriateness. (Everyone had seen me go to pieces when the coffin was brought in, so they had reason to know that I felt more than I was showing at that moment.)

We got back in our cars to follow the hearse to the cemetery. Traditionally, this procession is done on foot, but it was a long way, especially in the rain.

Mauro, who well remembered the privations of WWII and had no patience with useless expenditures, had expressed a preference to be buried the cheap way – in a vault. These vaults are very common in cemeteries in some parts of Italy, where space is at a premium and being buried in the ground therefore very expensive. It’s a condominium of the dead, an open-air building with walls containing 8 columns by 4 rows of slots, each slot with an opening about a meter square, and three meters deep. Mauro’s slot was on the top row, so a rough platform had been erected to allow the pall bearers to lift, tilt, and slide the coffin in – a procedure which risked degenerating into tragedy or farce.

An employee of the graveyard closed the opening with bricks and mortar. (I hated this; I felt claustrophobic.) He then put on a smooth layer of concrete, and stuck up a laminated paper sign with the name and dates, as a temporary headstone. Later, a made-to-order marble panel will be placed over this. Some of the friends and neighbors who had accompanied us put small bunches of flowers at the edge of the vault (rolling staircases are provided for tending the higher slots); the rest of the flower arrangements were piled on the floor below.

Then we all went home. We had a family dinner with the cousins who had come for the funeral, and that was it. No party, no wake. I think the Irish have it right on this one – you really need a big blow-out, to release tension and to celebrate, rather than mourn, the life that has passed. But it’s not the done thing here. Ah, well. There will be a memorial service sometime later, probably in Rome, so that Mauro’s many colleagues and students can pay their respects and share their memories of this remarkable man.

Aug 23, 2004

Many thanks to those who wrote condolences for Mauro’s death. I think I responded to everyone individually but, in case I didn’t – thank you. A few people wanted to know more about Mauro. I am working on a follow-up article about who he was and why so many people loved him, but I’m not sure that I’m psychologically ready to complete that one yet. This kind of grieving is new to me, and it’s harder than I ever imagined.