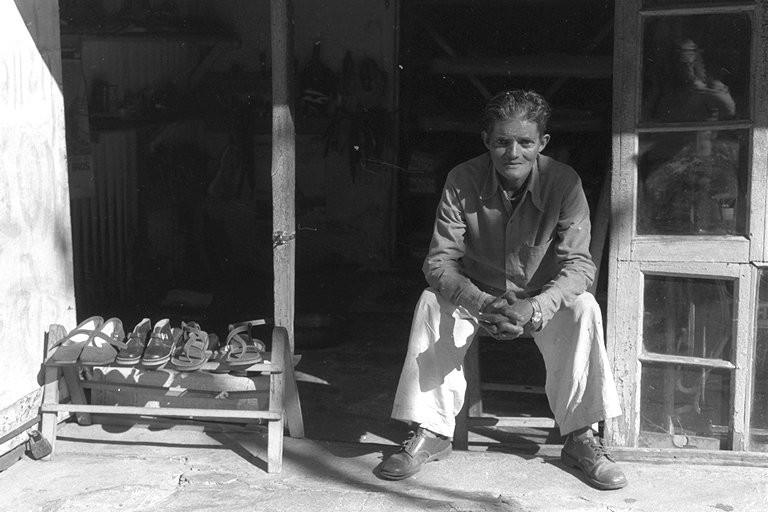

^ Buduram the mochi (shoemaker), Landour, Mussoorie, 1980

When I first went to India in 1977, there wasn’t a lot to buy anywhere in the country. The basics – food, clothing, shelter, transport – were all available, but the consumer goods industry was severely undeveloped, thanks to a government attitude of “Be Indian, Buy Indian”, enforced by high import tariffs and strict foreign exchange controls.

You bought food (and many other staples) at street stalls or open-air markets, or from vendors who came to your door with baskets on their heads – there was no such thing as a supermarket, and very little packaged food. Milk, for example, you got from a local dairyman who brought it to your door, fresh from the cow that morning, in a tin container with a measuring cup. (In cities there were dairy cooperatives which aggregated the output of many small dairy farmers.) You had to pasteurize the milk yourself by boiling.

^ milk delivery in Mussoorie, 2007 – not much has changed

The variety and quality of foods was limited, especially in smaller towns like Mussoorie.

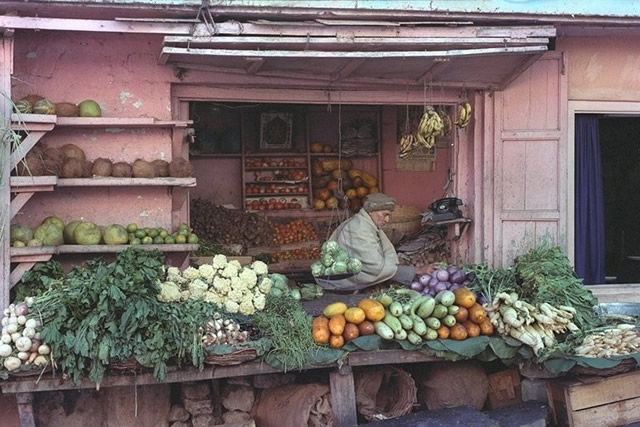

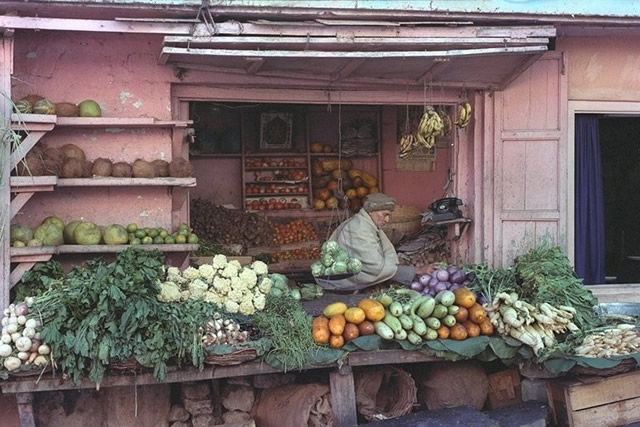

^ subziwallah (vegetable seller), Mussoorie, ~1981

Shops, even in Connaught Place (then Delhi’s poshest shopping area), were mostly dim and frowsy. Once you had exhausted your need or desire for gorgeous hand-woven textiles and other handcrafted items (of which the Indian middle-class consumer already had quite enough, thank you – these things look far more exotic when you don’t live there), there simply wasn’t a lot on the shelves. The branded goods available were few and poorly packaged, nothing like the overwhelming slickness and variety available in the US.

The first time a modern American car showed up in Mussoorie (driven by a US embassy employee) in 1981, children ran up to look at themselves in the mirror-like surface. The two models of car then available in India did not come with glossy paint.

Times Have Changed

On my recent visit to Mussoorie (which is still, in many ways, a dusty little town), I was astonished to see this:

It’s a retail store for Himalaya Herbals, a line of skin, hair, and personal care products and herbal medicines – very good ones, at prices which are, by my standards, quite reasonable. But Rs. 150 for a bottle of shampoo can be expensive for millions of India’s buyers – they have more money than they’ve ever had before, but still far less than you and I. Companies operating in India have adapted cleverly to this market, for example offering single-use packages at Rs. 1.50:

Food is available in far greater quantity and variety than ever before:

^ subziwallah, Mussoorie, 2007

What’s remarkable in the photo above are the fruits which were not even grown in India in the 1970’s: plums, grapes, apples, pears… I’ve also seen strawberries, nectarines, and out of season mangoes transported from south India to north. India is growing olives and wine grapes, and producing some decent wines (I like Sula‘s rosé).

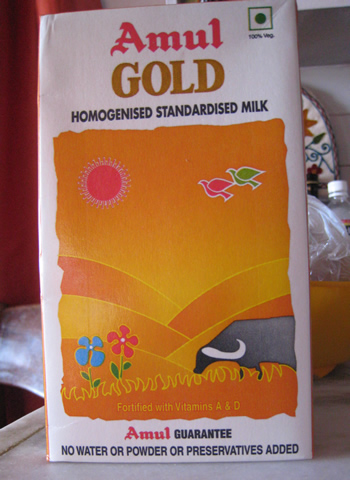

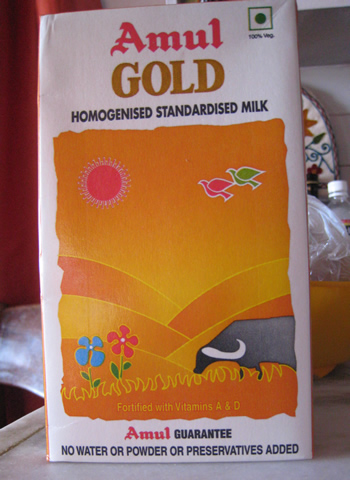

Though you can still get it from a local milkman, milk can also be bought in shops in tetrapak cartons, UHT-treated for a long shelf life. Amul Dairy was already a national company when I was in school, but in Mussoorie we knew it for butter, cheese, and chocolate, not milk. Note the water buffalo on the carton. Indians prefer the flavor of buffalo milk, which has a higher fat content than cow milk. (In Italy, mozzarella di bufala is considered the best for the same reason.)

There are national chains now: in the above photo, taken in Dehra Dun (the capital of Uttarakhand), you can see Habib’s (beauty salon), Himalaya Herbals again, and Café Coffee Day, one of at least three coffee chains in India today. Barista was bought last year by Italy’s Lavazza coffee company. There are supposed to be a few Starbuck’s outlets in India, but I never saw them. I did see Costa Coffee, another international café chain, in Delhi and Mumbai.

And there are shopping malls and supermarkets (this is in Dehra Dun):

In India’s large and mid-sized cities, you can buy many of the same brands (even at the same prices) that you’d find in any world capital, as well as attractive and well-made Indian brands. On the other hand, low-cost and hand-made goods are still easily available – the shoemakers in Mussoorie still make great shoes, and nowadays have more outside influences to inspire them:

^ mother-daughter cowboy boots, handmade in Mussoorie

As I keep saying: now is an interesting time to be in India…