Nov 12 – arrival in Delhi, 1:30 am

After the intense disappointment of not being able to attend my class‘ 20th anniversary reunion in Mussoorie last year, I wanted this trip so badly that at every step of the way I feared something would to prevent it. I was afraid I would be refused a visa (though there was no reason I should be), some major terrorist thing would happen, or that for some unfathomable reason I’d be refused entry at the airport. So, when I finally passed the immigration counter, I was light-headed with relief, and deeply happy.

I was met at the airport by my very reliable travel agency, Uday Travels. In India, especially if you’re a woman travelling alone, you need a good agent there on the ground. For each of my trips, I arranged in advance by email to be met at the airport by a car and agent, and most of my in-country travel was also arranged by them.

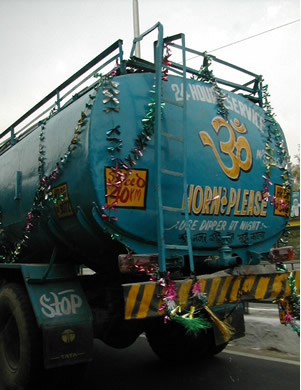

We drove from Delhi airport to Gurgaon, where I’d be staying with a classmate and his family. The traffic heading into Delhi at that time of night is horrendous: miles of trucks, which are only allowed into the city after midnight, and must pass a security checkpoint. We were fortunately going the other direction, but it was difficult to cross the line of traffic to get into the lane going the other way. India drives on the left, by the way. Roadside dhabas (snack stalls) vie for the truck drivers’ custom with huge, backlit signs and colored neon lights. The names are Hindi, but in roman script: “Manju ka Dhaba.”

My cellphone works! I was able to exchange SMS (text) messages with my husband and daughter. Being able to communicate more easily I hope will reassure them about my safety here.

Gurgaon used to be a small town in the state of Haryana. It is now a suburb of Delhi, calling itself “The Millenium City,” and it’s booming. Many multinationals, anxious to escape the crowding and expense of Delhi, have set up their regional headquarters in Gurgaon. There are gleaming tall buildings equal to any in Europe, some of them architecturally very interesting. It’s after 2 am, but I can see people inside working. Some may be employees of India’s famous call centers, providing English-language customer support worldwide.

There are tall apartment buildings, sometimes clustured together in blocks. My friend and his family live in one of these. The building is very well designed, and completely different from any apartment building I’ve seen before. Rather than a hermetically sealed box, it’s all angles and openings, both horizontal and vertical, so that air and light flow into the interior. The apartment entrances have screen doors as well as solid doors, so you can choose to be open to your neighbors, which creates a feeling of community. Yet it’s far less noisy than our Milan apartment, and at night it’s completely quiet.

My friends’ apartment is on two floors, with an interior staircase and a large exterior terrace two stories high, a wonderful place to sit and chat and enjoy the evening air (even a bit too cool, this time of year).

I arrived there at about 3 a.m., and went to sleep with a smile on my face. I had finally made it back to India.

I slept til 11, and woke up very slowly. I read The Financial Times, a four-page pinkish paper. It included discussions on tax reform, and simple and useful advice for investors. It’s wedding season, so there was a financial guide for new brides, advising them to retain financial independence: “You’re walking on clouds now, but you never know what the future may hold.” Another article touted platinum as “the hottest trend, especially in wedding-related jewelry;” Indian brides are traditionally given expensive jewelry. As the guide for brides pointed out, this becomes the bride’s personal property.

From the balcony I can see a wild green parrot and a squirrel. I suppose the wildlife has not been entirely driven out of Gurgaon yet. There isn’t much of a view, though, due to smoke and haze. Visibility is maybe 2 km.

Milk is delivered in sealed plastic bags that look like little pillows.

Delhi is taking steps to reduce its horrible pollution. The daytime ban on trucks is one such. A new bus and underground metro system, due to launch December 26, should also help. (Delhi has had buses for years, of course, but the new ones will replace the old smokers that contribute so much to the atmosphere.)

In the afternoon I took a car into Delhi to try to find a gemstone to replace the one lost from my engagement ring a few days ago (it wasn’t a diamond, fortunately). I went to a fancy jewely shop in the South Extension market (sort of a mini-mall), and found it full of families buying wedding jewelry. The man told me that the only loose gems they had were diamonds, an investment that didn’t interest me. He said I’d have to go to Old Delhi to find loose gems of any other kind. That’s an expedition that will require some planning.

Another shop in the market sold music and movies, including Video CDs – full length movies on CD in MPEG 1 format – for about $4 each. I bought a few to see how they look on my DVD player at home. The Video CD format is popular throughout Asia; you can buy standalone Video CD players, I assume that the players as well as the discs are cheaper than DVD.

That evening several classmates and friends who happened to be in Delhi (or live there) came for dinner, so we spent many hours talking, reminiscencing, and laughing.

Nov 13 – Delhi to Dehra Dun

The next morning I had to get up early again to catch a train to Dehra Dun. The train wouldn’t even be at the platform til 7, but it was one of those situations where if you leave early you end up sitting around at your destination for an hour, and if you don’t, traffic sets in and you’ll be late. So we sat at the station, and I chatted with the tour guide over sweet, milky tea.

Standards have declined since I last took the Shatabdi Express. It used to have only one class, and my agent didn’t mention that there’s now an Executive Car, which costs twice as much ($14 instead of $7), but is a lot cleaner. So I was in second class, and was not much amused to find small cockroaches crawling around my seat.

The windows are tinted yellow, to reduce summer glare, so the heavy mist outside looks unhealthy (and, this being Delhi, it probably is).

By the time the train reaches the countryside north of Delhi, the sun is up and people are in view, mostly men out shitting in the fields. (Where do the women go?) More palatable views include ponds with birds: white egrets, and something with a gray body, white breast, and black head.

Signs and Portents

Though an ever-increasing proportion of the population speaks English, Indian signage has lost none of its unintentional hilarity. A few examples:

Tress Passers will be prosecuted.

Accident prone area – please drive slow.

Plants on sale – also on rent

“Real fruit se full” This tag line for a brand of ice cream is a weird mix of Hindi and English. The Hindi word se means “of”. But the construction follows Hindi grammar, so the sentence translates as “Full of real fruit.”

Traffic lights are the standard red-yellow-green; on some, the word “Relax” is painted onto the red light.

“Indian marble – looks Italian!”

more signs

Nov 13 – On the Shatabdi Express to Dehra Dun

Cockroaches aside, the Shatabdi is very civilized. We are first given bottled water and a newspaper, then served an early tea, with a thermos of hot water and two “tea kits,” consisting of a tea bag, sugar, and powdered milk. There is also a packet of two biscuits (cookies, to you Americans). At first I was afraid that this was all the breakfast we would get, and was glad I had brought along my own packet of biscuits. But after the first stop a full breakfast was served. I took the vegetarian option, which proved to be a spicy vegetable mix wrapped in mashed potatoes and fried (croquettes), served with spicy ketchup, and white bread with butter. And more tea.

Dehra Dun

We arrived in Dehra Dun, the end of the line, at about 1 pm. As soon as the train stopped, coolies (porters) swarmed aboard to take the luggage. Their uniform consists of a lunghi (a man’s sarong), red shirt, and turban, with a brass identification/license plate on a string tied to the upper arm or slung diagonally across the chest. One of them put my small bag over his shoulder and balanced my big bag on top of his turban. I ended up paying him 25 rupees (about 50 cents), considerably more than the official rate. Yes, I am a tourist patsy. After years of experiencing India as a poor student and having to haggle over every rupee, nowadays I just can’t be bothered. Especially when one rupee is worth all of 5 cents – so very little to me, but sometimes a lot to the recipient.

My classmate Yuti was on the same train, but we weren’t seated together, so we didn’t meet till we got off the train in Dehra Dun; she had to run down the platform to catch up with me and the fast-moving coolie. Outside we hunted for a taxi. To get from Dehra Dun to Mussoorie, you don’t want to use the official taxi office, because those taxis will only take you as far as Picture Palace bus stand at the beginning of Mussoorie, and you’d have to change to another taxi to get to Woodstock School on the other side of town. The total cost ends up being the same, but to avoid the hassle of changing, we sought out an unofficial Mussoorie taxi. Only official taxis are allowed to park near the station, so actually getting into the taxi was a business. We were taken in a three-wheeled scooter taxi to a little lane nearby, where we waited for our car, which turned out to be a very mini mini-van. We stopped for lunch at a restaurant in Dehra Dun, then headed on up the hill.

Mussoorie begins at about 6000 ft (2000 meters) up the first range of the foothills of the Himalayas. To get to Woodstock, you have to continue from there on a steep and winding road which runs up the ridge through Landour Bazaar. There are far too many cars nowadays, so there is always a traffic jam at the foot of Mullingar Hill (the steepest and narrowest part of the road); inevitably one or more cars have to back up and find ways to fit around each other; it’s like one of those puzzles where you slide the tiles around to get the numbers in order, and the fit is almost that tight! It can take half an hour to untangle the mess and get everyone on their way. On the whole it’s faster to walk, but not with luggage.

(Back when I was in school, when students arrived for the beginning of the term we would be dropped off at Picture Palace, where coolies would meet us to take our trunks, and we would walk from there to school.)

Uday Tours & Travel Pvt. Ltd

10/2459 Beadonpura, Karol Bagh

New Delhi [India]

Phone : 91-11-574 9207, 571 1278, 581 6352, 575 4840

Fax : 91-11-572 8103 or 575 7108

E Mail : uday@del2.vsnl.net.in & utt@ndf.vsnl.net.in

. Accent was again expected to be a problem, so for the first series our hero was made to sound ‘more Roman than Sicilian.’ For the second series, airing now, the accents sound quite Sicilian to me, though not so much that I can’t follow the dialog. Montalbano is wildly popular with all age groups, which seems to be having an interesting side effect: the Sicilian accent is now considered cool. My daughter and her Milanese classmates yesterday begged their school custodian, a Sicilian, to say ‘quattro’ (four), which he pronounces ‘quacchro’. He was baffled, and probably thought at first that they were making fun of him. But they explained that they like to hear him speak because he sounds just like Montalbano; then he was flattered!