We visited Nepal in 1969 or ’70, when I was about seven years old. The country had only recently been opened to tourism, after a Russian named Boris Lisanevich persuaded the then king that this would be a good source of income for his impoverished country. Boris himself ran the first hotel, called the Palace because it had formerly been one (later, and until his death a few years ago, he ran the famous Yak and Yeti). We were the only guests there in January, so Boris invited us up to his private apartment to celebrate Russian Christmas.

Boris’ apartment was large, with white-uniformed servants everywhere. He had a huge silver artificial Christmas tree loaded with glass ornaments. He also had a snow leopard cub, orphaned by hunters. The cub was small, only about knee-high to me, but well equipped with teeth and claws. It seemed to fear the Nepali servants, perhaps because they reminded it of the hunters who had killed its mother. Because I wasn’t Nepali, or perhaps because I was also small, and generally got along well with cats, it liked me. I spent an ecstatic evening petting and hugging it; it was and probably still is the most beautiful thing I’d ever touched.

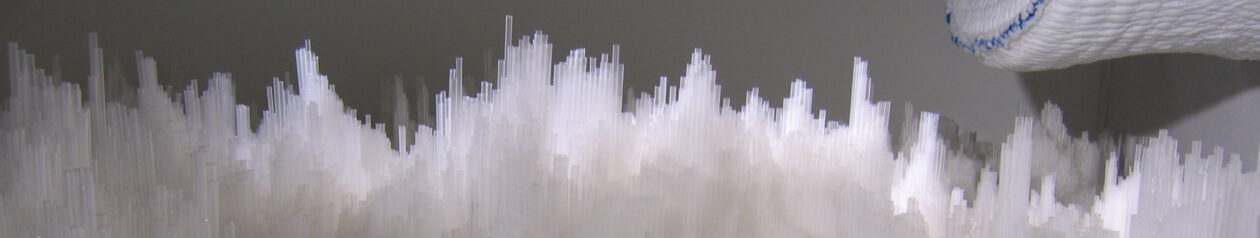

The cub only intermittently stayed calmly in my arms, however. At intervals it would go berserk and attack the silver Christmas tree. It would rush up the tree’s skinny metal trunk, so high that the tree would begin to bend under its weight. Then it would knock one of the glass ornaments to the floor, leap down, and eat it. A few minutes later it would vomit up a mess of thin broken glass.

Other memories of Nepal include my first experience of cold weather, and warming up by drinking sweet, milky tea, with arrowroot biscuits dipped in. (Tea seemed to me a very grown-up thing to drink.) And of course I saw Everest – from a distance. I was carsick on the drive up, vomiting out the window all over the side of the black Ambassador car, so I didn’t care very much by the time we got to there. In any case, we could only see a peak like all the others, so far off that it looked disappointingly smaller than many closer peaks.

Years later, in Mussoorie, I met Sir Edmund Hillary, then New Zealand’s Ambassador to India. He had come to see Everest House, a ruin a few kilometers out of town. The house had previously had a different name, but was renamed in honor of George Everest, because he had been living there when he finished the triangulations and calculations to determine that Chomolungma was the world’s highest peak – presumably he then modestly christened it with his own name.

Mar 24, 2004

I later learned that I had unjustly accused George Everest. John Keay’s The Great Arc: The Dramatic Tale of How India was Mapped and Everest was Named, explains that the British government named the mountain Everest to honor George Everest’s achievement in completing the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India. The data from this survey made it possible to identify the mountain as the world’s highest, but it also made many other things possible – and I highly recommend the book.

(Note: I don’t remember when this post was originally published on my old website – given the additional note at the end, it was clearly before 2004. I’m arbitrarily selecting today’s date in 2002, because it’s definitely one of my earliest posts. If there are any surviving photos of this trip, I don’t have them. Definitely none of the snow leopard, sadly.)