In January Enrico and I had one of our 15th anniversaries. May 28th was our other anniversary, the one we more often celebrate. Confused yet? Let me explain.

As I recounted in that earlier story, in the spring of 1988 we had decided that we should get married. We didn’t actually tell anybody about this decision til October, when we finally got around to buying a ring. Enrico bought the ring himself, to my specifications: not expensive, sapphire rather than diamond, something unusual. (Neither of us was rich, and I had never believed the deBeers advertising pitch about “two months’ salary – isn’t she worth it?” He was supposed to be marrying me, not buying me.)

So we became officially engaged in late October, on one of my weekend visits to New Haven, and I made a round of phone calls to let everyone know. My mother said something about wanting grandchildren, and my dad joked: “No hurry on kids – I’m too young to be a granddad!”

We polled friends and family about when they could come to the US for a wedding. My dad was in Indonesia, my mom was in Iowa, Enrico’s family and most of his friends were in Rome, my friends were scattered all over the place. So finding a date when everyone could travel was not easy. We settled on the last weekend of the following May (1989). Among other reasons, Enrico’s parents would be on their way to Los Angeles for a conference (they were both professors of pedagogy), and could easily stop by on the East Coast for a wedding.

In November, I took off from Washington for Tanzania, where I would spend several weeks installing a desktop-publishing system at a training institute there, and teaching people to use it. I had done a similar job in Cameroon in August and enjoyed it very much, especially the people I was working with, but that’s a story for another time.

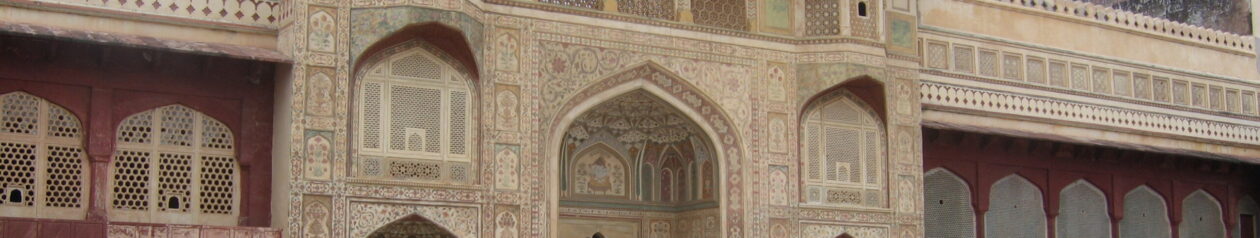

The Tanzania experience was not as fulfilling. My group of trainees, from various parts of East Africa, never quite managed to assemble for training, so once I had set up the equipment, tested it, and trained one or two people there at the institute, there was very little work for me to do. But Tanzania is much more a tourist destination than Cameroon, so I decided to take a weekend trip to some of its famous sites, the Ngorongoro Crater and Lake Manyara. I shared the trip and the expenses with an American woman and a Dutch man, and had a wonderful time, except that I hadn’t been feeling all that well, and by the end was feeling even worse – nauseated most of the time, which bouncing around in a Land Rover didn’t help. And my period was late. I had been putting that fact down to the stress of travel, jet lag, etc., but by now it was very late.

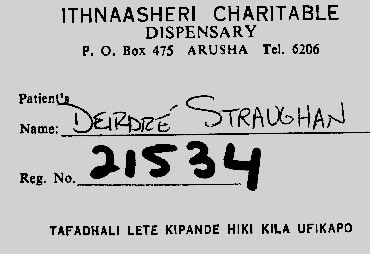

I finally decided to investigate, and asked someone at the institute if I could see a doctor. Their own doctor came only weekly, and I’d just missed his day, so they referred me to a clinic in town, for which they gave me no details except the address.

When I got there, I discovered it to be a charitable clinic run by a Pakistani doctor. Much of the clientele seemed to be Masai; when I walked in, a crowd of tall, regal women all turned to look at me – I was very much the shortest and whitest person around.

The doctor called me in, and I explained the situation. “Undress from the waist up,” he said. This in a room containing himself, his male assistant, and several women patients standing around, but they didn’t make a big deal of it, so neither would I (Masai women often go bare-breasted). I stripped to the waist and stood in front of the doctor. He glanced briefly at my breasts and said, “You’re pregnant.”

“Well, I figured. But can we do a test, just to be sure?”

So the next day I returned with a urine sample. The doctor’s assistant (not a Masai, he was about my height) took some in an eyedropper and dropped it onto a test card, which the spots of urine turned from black to green. We huddled over it together for a minute, but nothing else happened.

“You’re pregnant,” he said.

“How can you tell?”

“If you weren’t, it would go all dotsy-dotsy.”

No dotsy-dotsy. I was definitely pregnant.