We arrived in Sydney on Dec 23 – a day later than originally expected, but that was far, far less delay than many have suffered. As I was filling out the immigration card just before landing, it was an interesting feeling to tick “Yes” for “intention to permanently emigrate.”

Though there were only about 40 passengers on the plane, before landing we were asked repeatedly to allow plenty of space when deplaning. While we were taxiing to the gate, we were told that we would be met and given instructions by a health official, and should stay in our seats for the time being. Then it was announced that there would be a further delay because another flight had come in just before ours, and we had to give those passengers space in the terminal.

I settled in, expecting a long wait, but it was only a few minutes before we were told we could start to leave. Our family was in rows 35 and 36, a bit more than halfway down this A350, though we were seated the the furthest back of anyone on the plane – the whole rear section behind us was completely empty.

Having read accounts in the Facebook quarantine group about the airport arrival experience, I expected this, too, to take a long time. We walked a long way through the terminal, and any place where we could have strayed from the mandated path was guarded. (But that’s usual in airports.) We moved along, sometimes being held to maintain distance from the previous group of passengers.

We slowly worked our way down a corridor to where half a dozen medical personnel waited to interview us about our health. Our cards were marked, then we were sent back down the corridor we had just come through. Our passports were examined together, and all four of us – two Aussies and two more-or-less Americans – were quickly nodded through.

Then on to baggage claim, where we were relieved to find trolleys available – between us we had 10 suitcases of various sizes. All our bags had already arrived and been pulled off the carousel. We loaded three trolleys and went on through customs, where we had to put all our bags and carry-ons through an x-ray machine.

Lodging

Just outside the terminal, we were awaited by fresh air, sunshine, and more police, whose job was to assign our accommodation.. We explained that we are a family of four. Three adults and a child? This confused the policeman. “These two used to be married” – I pointed at Brendan and Claire – ”and this is their son [Mitchell]. Now he and I are married [pointing to myself and Brendan] and Mitchell is my stepson.”

“And you’re all traveling together? Fantastic!”

The policeman smiled, said something to his colleague with the list, and told us “Just get on that white bus.” Almost everyone was being put on the same bus. This confused me because Mitchell had been the only child on the plane – everyone else was adults, traveling solo or in pairs, and I had heard that solos and couples were being put up in hotels, while families, particularly with small children, had apartment-style accommodation. This was a huge point of worry for us. Hotels mostly don’t have windows that you can open for fresh air, and in some cases people were being put in rooms with little or no sunlight, or a view of a wall. No one gets a choice about where they stay (though in most places there are paid upgrades available, I hear).

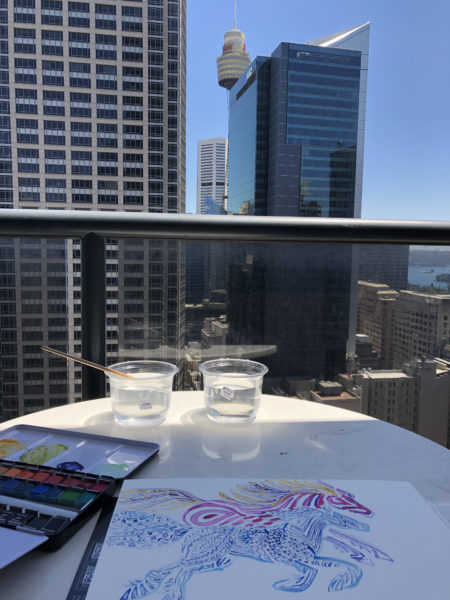

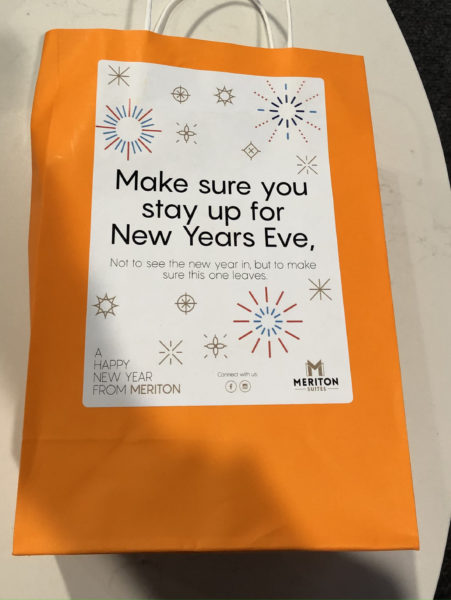

It had taken us about an hour to get from the plane to the bus: far less than I had feared. We were in the bus for another 40 minutes or so, and definitely heading to Sydney CBD (Central Business District, aka downtown). Eventually we stopped at the Meriton Suites on Pitt Street, which I knew to be a family-style accommodation. An official boarded the bus to ask who was the family, and took Brendan off (“Just the father, please”) to register us and answer questions. Claire, Mitchell, and I sat on the bus while our luggage was carried in by Australian Air Force personnel. After 15 minutes or so, the three of us were escorted by a nice young man in a uniform to a cordoned-off elevator and up to our suite on a high floor. We opened the door and explored delightedly: two bedrooms, two bathrooms, a kitchen/dining/living area, and a laundry room. The main rooms all faced onto a long balcony with floor-to-ceiling windows looking over downtown. I started laughing because directly in front of us was a building I recognized: 2 Park Street, many floors of which are occupied by Amazon Web Services. We won the quarantine lottery: we couldn’t have asked for better accommodation.

Food

I had been forewarned by the Facebook quarantine group that food might be a problem. The upside to staying in a standard hotel is that most of them seem to be going out of their way to provide really good food for their guests, and to promptly bring up any goodies that guests choose to order from outside. The Meritons have kitchens in the individual suites, but the hotel itself has no food facilities (naturally), so meals are provided by a central caterer. I’d heard horror stories (and seen photos) about how bad this catering could be. Our alternatives would be limited: Brendan relayed instructions from the hotel management that we should not order in more than once or twice a day, and that they couldn’t guarantee when anything ordered would be brought up to our room (ie, hot food would not arrive hot).

Not long after we arrived in the room, there was a knock on the door. By the time we opened it, the knocker had disappeared, leaving behind brown paper bags full of food: Sandwiches. Multiple plastic cups each containing two hard boiled eggs and some spinach leaves (helpfully labeled “Egg and Spinach”). Plates of crackers, fancy cheeses, and dried fruit. Salads with chicken and avocado. The next day’s breakfast arrived soon after: cereals, fruit, and two liters of milk. Instant coffee (International Roast – famously awful) and teabags.

Brendan had told the check-in staff that I’m allergic to peanuts and soy, so we always got at least two bags per meal, one containing stuff that I could safely eat, though there wasn’t always an obvious difference between my meal and anyone else’s, nor an ingredient list to tell me what I was avoiding in the others’ meals. If it seemed safe and we preferred each others’ food, we swapped.

The thrice daily meal deliveries became the highlights of our days – at least they provided an element of surprise, though after a few days we had already reached the stage of: “Oh no, falafel again.”

In spite of all the stories, the food was mostly decent-to-good, and very abundant. We were given far more fresh fruit than we could eat, and more salads than we usually eat. After many months of struggling to obtain food without endangering my health (I had not been inside any kind of shop since March 17) and having to buy, plan, and cook it all myself, it was a relief to have all that taken care of: food simply appeared three times a day, each of us ate what we wanted when we wanted, and no one had to think about it much.

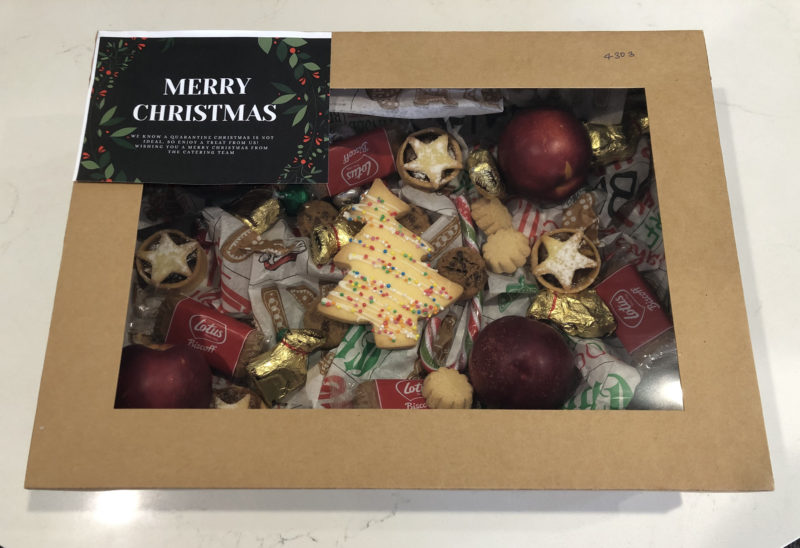

The caterers provided special meals for Christmas and New Year’s – turkey dinners, and then some nice fish meals (barramundi and salmon). By the end of the two weeks it all began to pall – there’s only so much you can do when catering food that has to travel from a central kitchen and then be microwaved. For reasons I never figured out, a lot of it gave me ferocious gas – not ideal in close living quarters!

We supplemented the catered food with a few grocery orders, including Aussie goodies we’d been missing – Tim Tams, Vegemite (yes, I actually like it!), Mersey Valley cheese, ginger beer. There were strict limits on alcohol deliveries – one bottle of wine and one 6-pack of beer per day, no hard spirits. From the Facebook group, I knew to expect this, and had assumed it was to prevent people drinking themselves into a reckless state out of sheer boredom. But someone in the group later pointed out that it’s also intended to curb domestic violence, which can all too easily be a problem when people are locked into a room together for two weeks.

Medical

On Day 2 (Christmas day), two medical people wearing PPEs and masks showed up at our door for our first COVID tests. We are so in the habit of putting on masks as soon as anyone knocks that we were instinctively reaching for them when one of the nurses said “You don’t have to wear those, because we are.” (We would have had to take them off anyway.) They stuck swabs down our throats and up our noses. It was uncomfortable but not painful, and simply left me feeling like I needed to sneeze. We were told not to expect to hear results unless one of us tested positive: “No news is good news.”

We were supposed to be getting a call every day from the nurse, to check in on us generally and ask if we had any symptoms. We realized within the first day or two that the hotel phone was not working, so I used my cellphone to call reception, and asked them to give my number to the nurse. Still no calls. On Day 3 or 4 a policeman knocked at the door to ask why we hadn’t been answering the nurse’s calls. By this time Claire had a working local cell number, so we gave that to the policeman and thereafter got our daily calls from the nurses. (Claire asked during one of those calls about test results – Day 2 tests came back negative.)

I also got a call early on from someone in mental health asking if we were all ok, and letting us know that we could call back anytime if we needed support. The health authorities were touchingly concerned about our state of mind.

Keeping busy

By the time we reached quarantine, we were so tired from all it had taken to get there, and so grateful to be in Australia, that we weren’t inclined to complain about anything. Our days didn’t feel very different from much of the previous 9 months in California. Brendan and I worked some. We all spent a lot of time on our devices, playing games, or reading. I watched a few shows. I had packed card games, but we’re not much of a table games family. On one of the few sunny days, I did some watercoloring out on the balcony. We ate, slept, chatted idly, and watched cricket on TV (Brendan was very happy to be able to watch the Boxing Day test match live).

Brendan enjoying the view and the sun on the balcony

Real weather – Sydney has a lot of it!

Watercoloring on the balcony

We were in quarantine through Christmas and New Year’s, which would have been devastating to many but was not that big a deal to us – even our normal Christmases are low key, and mainly for the benefit of Mitchell. Brendan and Claire had made sure that he would have presents to wake up to, and the caterers and hotel staff also did what they could to make the occasions special.

Getting out

On Day 10 we were tested again by two cheerful nurses. We weren’t informed of the results, but once again no news was good news. On Day 13, a group of medical and police people showed up to give us our discharge papers (we would need these at the next place we checked into) and wristbands that would allow us to check out the next morning, as early as 4am (I guess that would be useful if you had an early flight to somewhere else in Australia).

It all got boring by the end and we looked forward to being out, but all in all we had a good quarantine experience. Frankly, even without quarantine I’m not sure we would have done much other than rest in a hotel for the first week or so anyway.

I had read in the Facebook quarantine group about others’ experiences of getting out of quarantine and suffering PTSD – that after so long in isolation it felt strange and dangerous to be around people. But, more recently, someone else had pointed out that, for many of us, it wasn’t just quarantine, but also everything that came before – months of isolation, fear, and trauma. I was indeed feeling a lot of things during quarantine: gratitude and relief to be here, fear and sadness for my loved ones still in the US, and survivors’ guilt that I had left them behind. I had not yet even begun to process the fact that I had just up-ended my life – again – to follow a man to a new country.