I visited the Taj Mahal two or three times on school trips, between 1978 and 1981. Although by far the most famous site in India, it wasn’t terribly crowded in those days (except with that scourge of all Indian tourist sites: hawkers trying to sell you things). Visitors could wander at will all over the main building and grounds, and the guides would take you down into the lower mausoleum and point out the scar where a gigantic gem that originally decorated the small marble tomb had been stolen by the British.

My best memory of the Taj was an unusual one. On one of these school trips, though our group had already visited during day, two or three of us, on a whim, jumped into a cycle rickshaw and asked to be taken back that same evening. It was dark and raining and no one else was there – just us and three guards, carrying lathis and wrapped in shawls over their khaki uniforms. I don’t remember whether the site was even technically open to the public that night, but they let us in and gave us a special tour, showing off their own considerable knowledge of the Taj. Among other things, they demonstrated that one person could sing a chord inside the dome, thanks to the timing of the echoes. (You couldn’t have done that during normal hours – too many people inside to hear one voice over the din.)

Although I began to travel to India again regularly from 1996, I somehow never went back to the Taj, perhaps because I did not want to sully memories like these. When I was setting up the trip I took with Brendan in 2011, I didn’t originally plan to include the Taj – it wasn’t very convenient to our other stops. But he wanted to see it, so I rearranged things and made it fit into our schedule. And I ended up being glad I did.

We hired a car and driver to take us from Kesroli, in Rajasthan, to Agra: only 150 km by car, but… everything takes longer in India. We left early in the morning and arrived in mid-afternoon, with a brief stop at Fatehpur Sikri. The tour company had insisted on providing a guide, which we hadn’t really wanted, but he turned out to be useful.

The Taj is still the most popular tourist destination in India, but it’s now also one of the best-managed. To reduce pollution damage to the delicate white marble, all automobile traffic is stopped some distance away. You park your car, buy tickets, and then are taken in electric buses to the entrance of the grounds. The broad street leading up to the gate is lined with shops and eating places, but there are no more pushy tourist touts – a pleasant change!

As foreigners, we were “high value” – we’d paid ten times as much as Indians (still only about $50). At least we got our own security line (but none of the lines were long when we arrived). Before entering the grounds, everyone goes through metal detectors and is frisked, bags are inspected and all food, drink, and chewing gum are confiscated.

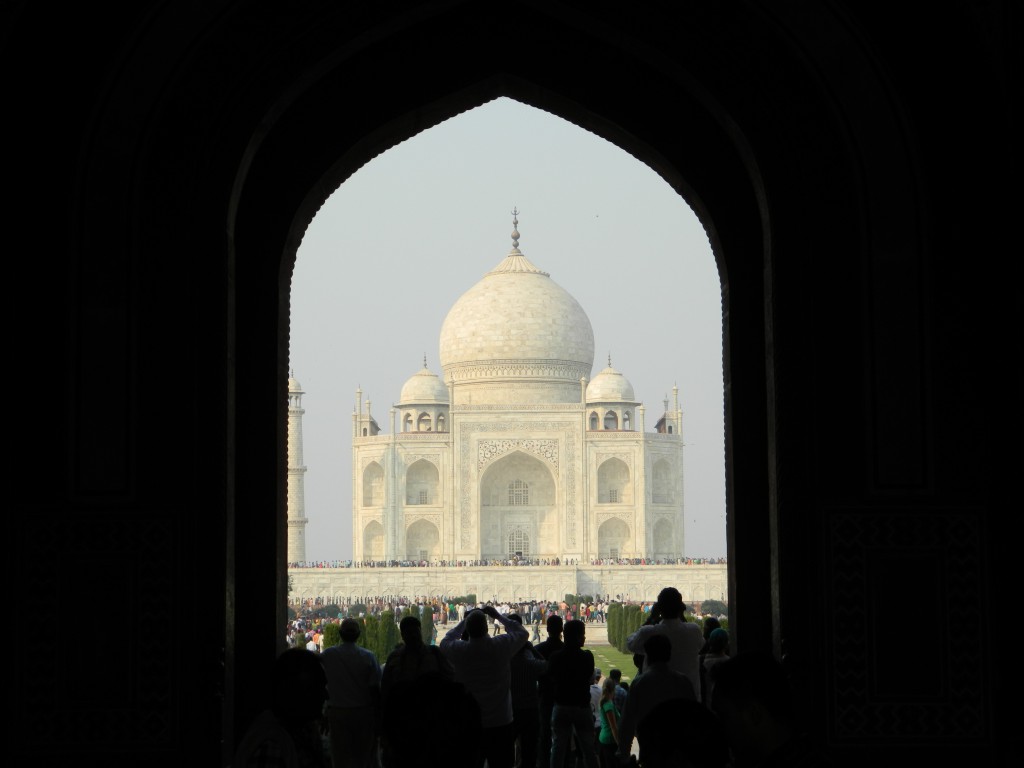

Inside the gate, we found the place stunningly crowded, far beyond my (possibly faulty) memories.

I don’t like crowds, but, as we got further in I became fascinated by the composition of this one. The tourists thronging the Taj today showed a far higher proportion of Indians than I remembered. Our guide said that this was because we were there in the afternoon – the foreigners tend to go to the Taj in the morning, the Indians in the afternoon. “You were smart to come in the afternoon,” he added. “In the mornings this time of year there is often fog, so you can’t take good photos.”

I was smugly pleased by my own foresight: I had in fact planned the trip so as to arrive in the afternoon, because I love photographing in the long, golden evening light:

The interesting thing about the Indian crowd was its diversity. People from all of India’s regions, religions and social classes were represented, all enjoying a holiday trip (it was Diwali, a major Hindu festival) to one of their country’s great monuments. Clearly, such travel is within reach of many more Indians these days, a happy sign of economic progress.

Sadly, bigger crowds mean more restrictions. We had to stand in a long line to go up the stairs and into the main mausoleum. You then get rushed through and are not allowed to photograph inside. Even the bad photo at the top of this page, taken on a compact camera around 1980, would not be possible today.

But the Taj is still beautiful, and even standing in line was interesting: it gave me more insight into changes in Indian society. The line snaked across a plaza at ground level, organized by security guards. When the guards’ backs were turned, people would try to cut from one turn of the line to another. Our tour guide took it upon himself to behave as line monitor, barking at them to get back to their places, with others loudly seconding him. A Brahmin (identifiable by his dhoti, sacred string, top-knot of hair, and forehead mark), casually walked into the middle of the line – and everyone yelled at him until he went back to his starting place. I found this telling and amusing; Brahmins no longer have the privileges their forefathers enjoyed.

Later, when we were up at the tomb entrance level, the line below deteriorated and nearly became a riot:

but the guards moved in quickly to restore order.

Once we’d got through the interior, we were free to stay and enjoy the beautiful evening.

Brendan helped me recreate a picture that had been taken of me at the Taj in 1980:

Note the cloth booties, which we were required to wear over our shoes. I should have chosen the alternative – checking our shoes at the racks on the way in (you used to just leave them piled up on the stairs and tip somebody to keep an eye on them). The feel of sun-warmed alabaster under your feet is a sensual treat that I’m sorry I missed this time.

On the way out, we posed for the classic Taj tourist shots:

Sounds great Deirdre but the crowds put me off – there was a time when they didn’t but now …

Cheers,

Janet

What great set of photos, showing the Taj in all its moods, beauty, uses, activities, etc.Thanks.